Wentworth Woodhouse, one of Yorkshire’s architectural gems, can be seen again as 700 tonnes of scaffold comes down after 18 months.

Wentworth Woodhouse, one of the grandest of Yorkshire’s stately homes, emerged in its renovated state in January from the 700 tonnes of scaffolding it has spent the past 18 months wrapped in.

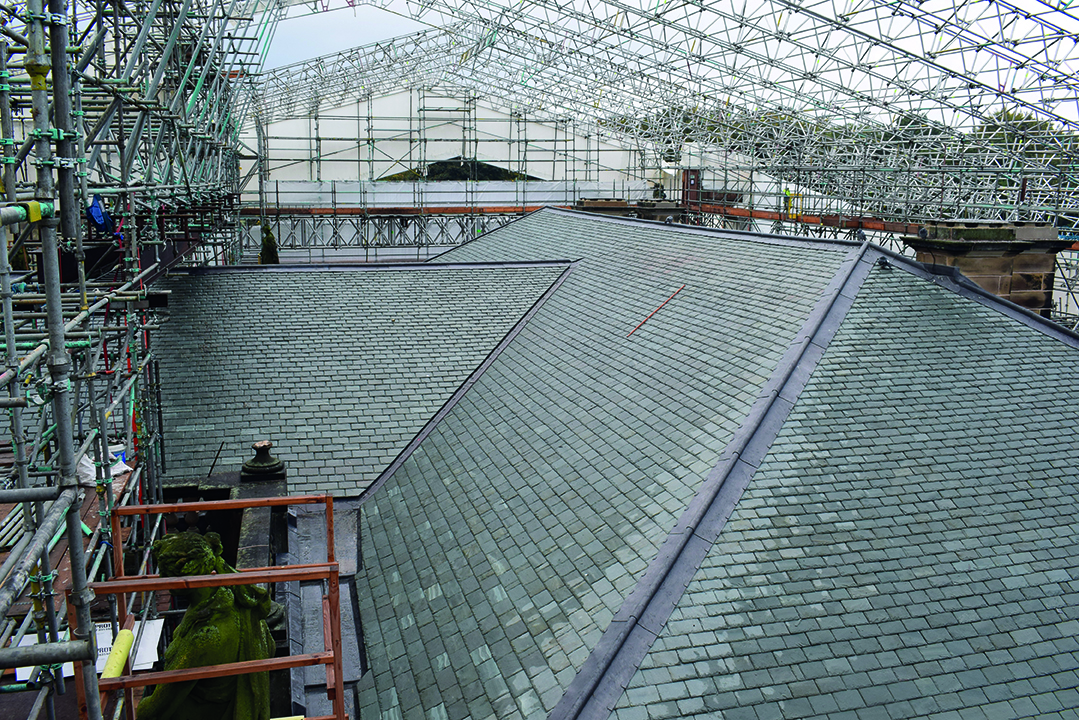

Behind the shelter of the temporary structure’s covers, roofers from Martin-Brooks (Roofing Specialists) and stonemasons from Heritage Masonry Contracts worked with main contractor Robert Woodhead Ltd of the Woodhead Group under the guidance of the architects from Donald Insall Associates to make the roof watertight and repair damage to the urns, sculptures and masonry that give the building its distinctive skyline.

For the roof, approximately 65 tonnes of new Westmorland Green Slates from Burlington have been used to match the original slates. To raise money, individual slates have been sponsored, with the donor’s name written on the back. Original slate that was in good condition has been salvaged and will be re-used on other parts of the Wentworth Woodhouse roofs.

At 30m high, the scaffolding consisted of 50,000 linear metres of scaffold poles. If they were stood on top of each other end to end they would be five-and-a-half times higher than Everest. They weighed 700 tonnes and held 6,000 scaffolding planks. The frame was covered in sheeting at the higher levels to protect the people working there from the worst of the wind.

At 30m high, the scaffolding consisted of 50,000 linear metres of scaffold poles. If they were stood on top of each other end to end they would be five-and-a-half times higher than Everest. They weighed 700 tonnes and held 6,000 scaffolding planks. The frame was covered in sheeting at the higher levels to protect the people working there from the worst of the wind.

The estate is managed by the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust. Its Chief Executive is Sarah McLeod, who moved into the post when the Trust took over responsibility for the buildings and the 87-acres of gardens and parkland that surround it in 2017. By then it was in urgent need of repair, especially to keep the rain out.

The Trust took over after Phillip Hammond, then Chancellor, had allocated in the autumn statement of 2016 £7.6million to repair the roof. The Trust had appealed to government for help and received it through the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport with funding administered by Historic England, which was closely involved in overseeing the work.

Once the scaffolding was up it became clear more work was needed than had originally been budgeted for. Notably, the cornices needed repairing, so the Trust had to raise an extra £350,000 just for that. The scaffolding had cost so much it made sense to do the work while it was up.

Louis Harrison finishes the installation of a new cornice. He’s starting his fixer course formal training this year.

Louis Harrison finishes the installation of a new cornice. He’s starting his fixer course formal training this year.

The cornicing was paid for by donations from Historic England, various anonymous donors, the Freshgate Foundation, the Leche Trust, and the Liz & Terry Bramall Foundation (created by one of the wealthiest families in Yorkshire).

Sarah McLeod is delighted the funding included the Yorkshire family because she says the house is about Yorkshire. Rotherham is an area with ambitious plans for regeneration and growth and the opening of the house will benefit the local economy by bringing in visitors from all over the world, without excluding those from the local community.

As the work was carried out last year, stopping only for a few weeks of the first lockdown, thousands of people, locally and from further afield, took advantage of the opportunity of taking a guided tour and watching the work being carried out from the public viewing platform.

The coronavirus might have deterred some people from climbing the 135 steps to the viewing platform (although there were also two accessibility lifts) but even so there were four or five suitably socially distanced tours most days with around 10 visitors in each group. “For us it’s nice to see the public taking an interest,” says Sean Knight, the Managing Director of Heritage Masonry Contracts.

The grounds, inhabited by deer and other wildlife, are a popular recreational space for the local population and visitors.

The previous owner of the property had put it up for sale by the time the Trust took it over. It became clear to the Trustees that work had to be carried out urgently or “it was going to fall down, there was so much water coming in”, says Sarah McLeod. She says the trades involved in the work “have done an absolutely fantastic job.”

She especially likes the fact that Sean Knight’s Heritage Masonry Contracts had apprentices on the project because training is part of the ethos of the Trust’s plan. Sarah praised the stonemasonry team not just for the quality of their work but also for being “fantastic communicators”.

“When something needed to be sorted out they sorted it out, all working together. Sean never once said ‘sorry, I’m on holiday’ or anything like that. Even when he was on holiday he still came in if he was needed.

“They were thinking all the time not how much money can they make but how they could get the job done. It was about being a team and working together.”

Irene is a Roman goddess with a hefty infant in her arms. She was repaired with several stone indents and carefully colour-matched mortar repairs so they would be unobtrusive. Her waist had eroded and she had to be pinned back together with stainless steel. There is a steel bar on her back to stop her toppling over due to the weight of such a large infant.

Irene is a Roman goddess with a hefty infant in her arms. She was repaired with several stone indents and carefully colour-matched mortar repairs so they would be unobtrusive. Her waist had eroded and she had to be pinned back together with stainless steel. There is a steel bar on her back to stop her toppling over due to the weight of such a large infant.

Sarah came to the Trust from having been CEO at Cromford Mills in Derbyshire, a Grade I listed World Heritage Site. The renovation work there involved another stone and conservation company, Bonzers, based in Nottinghamshire, which she holds in high regard.

When Sarah left Cromford Mill the project had just won a Europa Nostre Award and she was wondering what she would do next. “I like being at the dirty end of these projects,” she says. Out of the blue she got a call from a head hunter for the Wentworth Woodhouse Trust.

When she took over at Wentworth Woodhouse there was a phone and a vacuum cleaner. In the three years since then she has built a business employing 52 people and recruited an army of volunteers. “We had a tight window of about five years to go from nought to 60,” she says.

It would not have been possible to build up slowly with such an extensive estate to administer as it had to start making significant sums of money quickly to pay for itself.

Sarah says the coronavirus even aided last year’s programme to some extent because the work on the roof involved the removal of asbestos, when the public would have had to be kept away. The lockdown made the closure easier.

During the pandemic restrictions the Trust has invested heavily on setting up a TV channel on YouTube and has made films about the conservation work. The house attracts a fair number of celebrities, some of whom they have managed to persuade to be interviewed for the TV channel. These ‘in conversation with…” programmes will join online lectures on the TV channel.

Various guided tours were available last year, ranging in price from £7.50 to £50 per person. Once the house is open to visitors again the tours will resume. “We want people to come and walk around and enjoy it,” says Sarah.

There are said to be 365 rooms in Wentworth Woodhouse – one for each day of the year – but it depends what you call a room. An architect has said there are more than 400 distinct spaces within the structure. However, that includes cupboards, although there are ‘cupboards’ off the state rooms that Sarah says are bigger than the living room in her own home.

It is the state rooms that will be open to the visiting public. But the building is described as being of ‘mixed use’, with some rooms for events and some for holiday lets and overnight stays. The Trust is also introducing Shepherds Huts in the grounds that can be hired by the day.

Wentworth Woodhouse is really two houses joined together. Its original entrance was the baroque west front, but the second Marquess of Rockingham, Charles Watson-Wentworth, who was briefly Prime Minister in 1765–66 and again in 1782, wanted the house to be a centre of Whig (Liberal) politics and Whigs did not like the baroque. So he had the east front built in neoclassical style, reorienting the main entrance of the house and leaving the west front to face the family’s private gardens.

There was probably also an element of rivalry with another part of the family, the Earl of Strafford, who lived in the nearby Wentworth Castle that he had had rebuilt in a magnificent manner.

The work last year involved 1,500m² of the roof of the main building – that’s the size of six tennis courts.

The work last year involved 1,500m² of the roof of the main building – that’s the size of six tennis courts.

At the peak of the works there were up to 30 people from various trades working on-site each day. The site continued working through most of the year. One member of the Heritage Masonry Contracts team did contract Covid-19 in August, although he quickly recovered.

The site had closed for five weeks during the first lockdown in the spring. During that time Heritage Masonry Contracts made two of the replacement urns needed, which left their schedule intact.

After the lockdown the masons travelled to site from their headquarters in Stamford in two vans, rather than the usual one, so if anyone in one group was found to have the virus there would still be another group to continue working. One team did have to isolate when one of them contracted the virus but the programme was maintained.

Sean praises the communication and fore thought of all involved from the Trust, lead architect Dorian Proudfoot and site manager Andy Stamford of Robert Woodhead Ltd for keeping the project on schedule and limiting the impact of the Covid pandemic on operations.

“When a decision was needed, it was made quickly,” says Sean. “Everyone was very sharp. I think the communication and a willingness to all work together were the key to the project’s success.”

Heritage Masonry Contracts’ work included stripping down the balustrades, replacing about 200 of the baluster bottles and repairing others with stone inserts or Roman cement.

The bottles were made of Howley Park sandstone, quarried by Marshalls. The building is mostly sandstone, but Ketton limestone was used for some areas of cornicing and balustrades. Ketton stone is still produced from Ketton by Hanson Cement, although for this project Ancaster stone from Glebe quarry was used where Ketton needed to be replaced.

The bottles were made of Howley Park sandstone, quarried by Marshalls. The building is mostly sandstone, but Ketton limestone was used for some areas of cornicing and balustrades. Ketton stone is still produced from Ketton by Hanson Cement, although for this project Ancaster stone from Glebe quarry was used where Ketton needed to be replaced.

The decision to use Ketton for the original build probably had something to do with the Marquee of Rockingham owning stone reserves at Ketton (Uppingham). You wouldn’t normally put limestone above sandstone because it leads to the deterioration of the sandstone – and the original builders would have been well aware of that. For the renovation work, Heritage Masonry Contracts replaced limestone with sandstone where it had been used above sandstone to eliminate the problem.

Chimneys were also stripped down. They are mostly stone clad with more stone inside, or sometimes brick. It’s thought the stone must have corroded so far back that the chimneys were re-clad at some time in the past with new stone. There were six-to-10 flues in each chimney.

The sandstone mouldings under the stacks were heavily deteriorated. They have been repaired using lime mortar with 1.25 parts river washed sharp sand and 1.25 parts soft sand, one part brick dust and one part lime.

It was one of several different mixes of lime mortar used in the project. It was mostly hot mixed, although on top of the chimneys

NHL 5 hydraulic lime was used because it cures quicker than hot-mix.

Different mortar mixes were used as appropriate for various uses, with pozzolans added as necessary. Being allowed this freedom with the mortars also allowed more mortar repairs to be carried out than might otherwise have been the case. But the use of plastic repairs has been selective.

Sean: “Where we know we will be able to get access on the roof without scaffolding we have made plastic repairs. Where we know we won’t be able to get access without scaffolding we have replaced the stone.”

Most of the work carried out was at high level and a lot of it was the result of damage from rusting iron clamps that had blown the stone. “We have worked on buildings 300 years old where the ironwork is fine because water has not got in,” says Sean, “but once water reaches the iron and it starts to rust, it forces the stone apart.”

Ben Halifax, who completed his level two training with Heritage Masonry Contracts at Wentworth Woodhouse, is repairing one of the urns. He is working towards his level three this year.

Ben Halifax, who completed his level two training with Heritage Masonry Contracts at Wentworth Woodhouse, is repairing one of the urns. He is working towards his level three this year.

All 19 urns were removed, each of them weighing around 650kg. Two of them turned out to be cast concrete, two were limestone and the rest sandstone.

Sean speculates that the original builders could not get enough sandstone to make all the urns, so they turned to limestone. They would have known putting limestone on top of sandstone is not generally a good idea as run-off rain from the limestone carries salts that cause erosion in the sandstone.

The urns that were concrete were replacements installed over the years. They have now been replaced by newly carved stone urns to match the others on the building, although the concrete urns have been retained for possible use in the garden at some point.

Some of the urns had been installed using timber pins, which had rotted, leaving the stone held in position by its own weight alone.

Lifting the urns down from the roof to be repaired was challenging as their centre of gravity was around the middle due to their shape, making them unstable. As historic objects, it was important not drop or damage them and after some head scratching it was decided to construct a scaffold frame around each urn to secure it while it was lifted. Extra clips were added to the frame to allow the crane crew to clip on and off more easily.

There were five sections to each urn and each section was chogged (tightly wedged) before they were dismantled by the masons. Some had been strapped with copper strips, although Sean says: “What good that would have done I don’t know. We could bend it with our hands.”

The urns were lifted back into position after restoration in sections on stillages (frames to keep them safe) and secured back in position using stainless steel dowels that are mortar grouted into the whole length of each urn to reinforce it.

The urns were lifted back into position after restoration in sections on stillages (frames to keep them safe) and secured back in position using stainless steel dowels that are mortar grouted into the whole length of each urn to reinforce it.

Once the scaffolding had been erected the masons found a lot of cement repairs that had been carried out over the years and had to be removed. The stone behind the cement was dust and had to be replaced. Because scaffolding is expensive, some work that was not urgent but would become so in the next few years was carried out so no more major projects are now required.

During the course of the project, Heritage Masonry Contracts’ contribution nearly doubled in size and Sean says they could have been there for a decade, there was so much stonework that could have been restored. Sean and his team are already back on site working on the north tower. “Our main aim is to help our clients care for their buildings with diligence and passion,” he says.

Some of the replacement carving was carried out on site, but with the public coming in and out to see the work being carried out and some of the stone being high crystalline silica content sandstone, much of it had to go offsite to be carved.

The date originally set for striking the scaffolding was mid-October, but it actually finished coming down just after Christmas, although that had more to do with the extra work carried out than the coronavirus.

Below. The ‘Covid bubble’ from Heritage Masonry Contracts. They are (left to right) Ben Halifax, Oliver Atkin, Louis Harrison, Sean Knight, Robin Emery and Ryan Whitehead.