More than a thousand years of English history are recorded in the stonework of Winchester Cathedral. An exhibition at the Cathedral explains how to read those stones.

Above. The statue of Alfred the Great by Sir William Hamo Thorneycroft, erected in Winchester in 1901 and still standing in the City. King Alfred laid the foundation for a single kingdom of England with Winchester as his capital.

Decoding the Stones is one of three major permanent exhibitions in the south transept triforium of Winchester Cathedral that together form Kings and Scribes: The Birth of a Nation.

Opened following the installation of a modern glass lift to provide easy access to the upper floors of the Cathedral, the stones unlock the mysteries of a building that has been created, destroyed and re-made over centuries of struggle and civil war in a city that was the capital of England for kings from Alfred the Great in the ninth century until the Normans transferred that status to London in the 12th century.

Winchester Cathedral is a Grade I listed ancient scheduled monument in Winchester’s Conservation Area. It includes important examples of all architectural styles from the Romanesque (Anglo-Norman) through the developed Gothic to Renaissance, a visual testament to the nation’s vibrant and sometimes turbulent history.

Kings and Scribes: The Birth of a Nation is so called because it was the Kings of Wessex, with Winchester as their capital, who defeated the Vikings and united England under the rule of Anglo-Saxons.

The Cathedral that stands today is essentially the work of the Normans with later additions. They built it on a site where a church had stood since the seventh century and the early days of Christianity in England. They used Quarr limestone for its construction, brought along the coast from the Isle of Wight. Quarr is the source of the word ‘quarry’ for the extraction sites of stones.

French masons had always been happy to transport stone by sea for their construction work in the UK, which is why so many historic buildings in the South of England have walls of French limestone, including Canterbury Cathedral.

Subsequent repairs and alterations to Winchester Cathedral have added a mixture of stones that include Beer stone, Doulting, Portland and Caen, resulting in a patchwork appearance in places.

It is not just the colour of the stone that differs but also the porosity, which has influenced the degree of weathering. The problem of different porosities of materials in close proximity has been most obvious where hard cements have been used with limestone, often for repointing or plastic repairs. But the effect is the same where a more dense stone is used alongside a less dense stone. Different stones also attract different species of lichen, which adds to the patchwork effect.

The tracery work to the windows added from 1200 to 1600 has been worked in French Caen limestone, which is still readily available for repairs. Caen would have been expensive to ship, which is probably why it has only been used for the more decorative parts of the building.

There are only three stonemasons working at Winchester Cathedral full time these days and they praise the quality of the original Quarr Stone. Will Davies, one of the masons, told NSS: “As a building stone it’s incredible. It’s largely shell with little bonding matrix and not particularly dense. It’s light and breathable and allows water to travel through it well. It is incredibly durable. The external Norman work seems as though it hasn’t weathered at all. When it’s cleaned it looks like it could’ve been worked yesterday, so we rarely have to replace Quarr.

“The St Cross Hospital is another good example of the use of Quarr. It’s just down the road from the Cathedral and built in the same Norman style, but has had fewer additions made to it over years, externally at least. It’s a lot smaller but gives an idea of what the early cathedral would’ve looked like. It’s well worth a visit.”

The masons collect as much of the Quarr stone as they can whenever and wherever it becomes available, because the quarry has long-since closed. They keep any stone removed from the Cathedral itself, because it can generally be re-used.

Will: “We had a lovely job lined up to open up a previously blocked-in pilgrims doorway in the North Transept to create a fire escape, with a surround that would be fitting for that part of the cathedral. I researched the closest matches to Quarr that we could use for this and found a couple of suitable stone types from the Purbeck area. Unfortunately this project was scuppered by Covid, so will have to wait for another day.”

The fact that the stone is so resilient and can be re-used explains some of the exhibits in ‘Decoding the Stones’. Some of the sculptures were removed during the Reformation, when Roman Catholic iconography was systematically hacked out of places of worship by the Protestants.

Some of the carvings in the exhibition come from the Great Screen, a soaring, ornate 15th-century stone screen behind the high altar, which is one of the most important monuments of the period.

The original painted statues that once adorned its carved niches were removed in the Reformation, but some of the stone was re-used and has been rediscovered over the years as repairs and alterations have been carried out. This now forms part of the new exhibition. The statues seen in the Great Screen today were added in the 19th century.

In investigating the work necessary to open up the pilgrims doorway the masons discovered what they believe could be remnants of Purbeck Marble used in the original Shrine of St Swithun, the Cathedral’s patron saint, that was smashed and ransacked of its treasures in the early hours of 21 September 1538 by the King’s Commissioners.

A modern memorial marks the spot where St Swithun’s shrine stood. A replica of the original, made from reconstituted materials, has been included in ‘Decoding the Stones’.

St Swithun was a counsellor to the Saxon kings Egbert and Ethelwulf and probably tutored the young Alfred the Great. Legend says he built the first stone bridge over the River Itchen that runs through Winchester. Certainly he was Bishop of Winchester for the final 10 years of his life up to his death in 863. He was initially buried but his bones were later dug up and housed in a reliquary. They became famed for their healing powers.

The reliquary was moved into the new Norman cathedral in the 11th century and an even larger shrine was built for the reliquary in 1476, festooned with gifts of silver, gold and jewels offered by wealthy pilgrims. It continued to attracted people to the Cathedral until it was smashed and plundered under the cover of darkness in 1538.

The new, permanent exhibitions at the Cathedral telling these and other stories mark the culmination of an eight-year development that has sought to unlock the building’s treasures.

All Britain’s cathedrals rely heavily on tourists, both national and international, to pay for their upkeep, and it had been hoped these exhibitions would help attract even more tourists this year.

Of course, like all the cathedrals, Winchester has suffered the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, having to shut during the lockdown in the spring and again last month (November) during the second national lockdown. The number of international visitors to the UK this year has been seriously curtailed.

The project that resulted in the exhibitions started in 2012 and encompassed the repair and conservation of the presbytery roof, high vaults and roof bosses, and 15th-century stained glass. It was made possible by a grant of £11.2million from what is now the National Lottery Heritage Fund and donations from other generous supporters.

The redevelopment of the triforium gallery as the new exhibition space was a major part of the work, creating a family friendly learning and participation space to encourage audience engagement with three key and interconnected stories: A Scribe’s Tale, Decoding the Stones, and The Birth of a Nation.

The construction of the Wessex Learning Centre and the refurbishment of the Education Centre has greatly enhanced the quality of the Cathedral’s education and outreach programme to what would normally be more than 25,000 children annually from Hampshire and beyond, as well as enabling all-age learning.

It has transformed the South Transept into a fully accessible state-of-the-art exhibition over three levels – with that accessibility to the mezzanine and triforium floors being provided by a new Stannah glass lift.

Other cathedrals that have sought to install lifts have met with opposition because of the impact on ancient structures. Winchester gained permission even though the lift rises through a 1,000-year-old vaulted ceiling. For some, there was a silver lining in that the direct-acting hydraulic drive of the lift necessitated an excavation, which revealed the flint and lime foundation work on which the cathedral is built. And the glass walls of the lift offer unusual views of the Cathedral’s interior.

John Crook is the author of an informative book called Winchester Cathedral, which is a bargain at £10 from the Cathedral Shop, even when it is bought online with a few pounds added for postage. It was he who made an excavation a couple of metres below ground level and revealed a corner of one of the flint and lime foundation ‘pads’ the main columns were built upon. It gave an indication of the preparatory groundwork the Norman builders carried out prior to starting the construction of the columns and walls.

Even so, the Cathedral is built in the valley of the River Itchen on peaty soil with a high underlying water table. By the start of the 20th century serious cracks had opened in the walls and vaulted ceilings – some apparently wide enough for ‘owls to roost in’. Stone had begun to fall and there were fears the building would collapse, especially when efforts to underpin the waterlogged foundations failed because trenches dug to carry out the work simply filled with water. Even steam pumps could not keep them dry.

William Walker, a deep-sea diver, came to the rescue. He worked at depths of up to 6m every day for six years to excavate the flooded trenches and fill them with bags of concrete. He was working blind, feeling his way with his bare hands, because the water was too murky to be able to see anything.

When he had finished, it was possible to pump the water out of the trenches so the subsiding walls could be safely underpinned by bricklayers. In recognition of his work, there are two sculptures of him at the Cathedral.

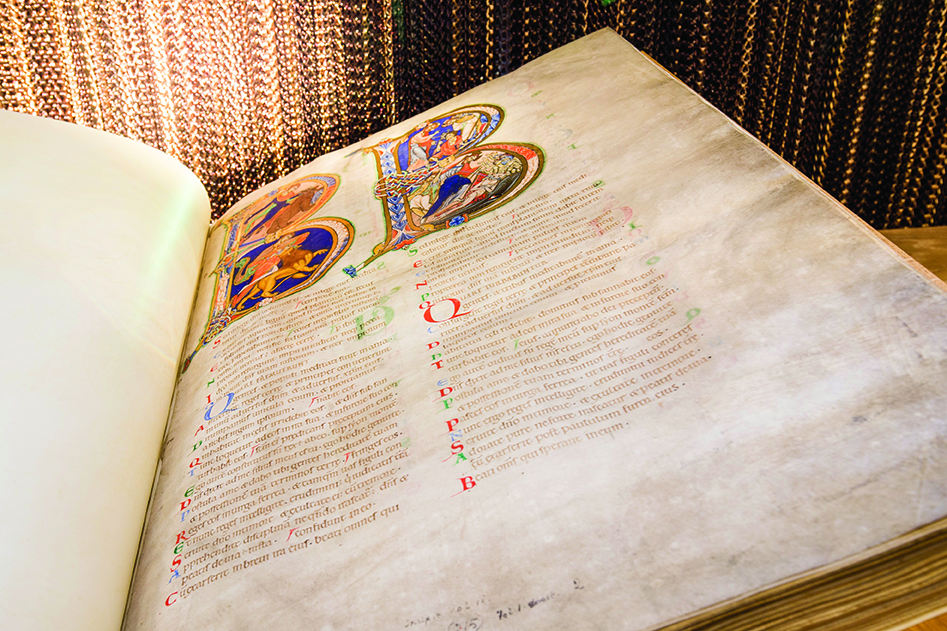

Kings and Scribes tries to leave as many of the exhibits as possible out in the open, although some are behind glass for their protection, such as the grandly illuminated 12th century Winchester Bible and the bones of Emma, the wife of two kings (Ethelred the Unready and Canute) and the mother of two more (Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor). Most of the other ‘bones’ on display of kings and bishops from the Cathedral’s unique mortuary chests are 3D printed replicas.

Kings and Scribes tries to leave as many of the exhibits as possible out in the open, although some are behind glass for their protection, such as the grandly illuminated 12th century Winchester Bible and the bones of Emma, the wife of two kings (Ethelred the Unready and Canute) and the mother of two more (Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor). Most of the other ‘bones’ on display of kings and bishops from the Cathedral’s unique mortuary chests are 3D printed replicas.

There is more from archaeologist and author Dr John Crook about the excavations that contributed to the exhibition in the next issue of Natural Stone Specialist magazine.

The pictures below give an idea of the exhibition and the Cathedral. The first picture shows the top of the new lift behind the base of the original 7th century altar of Old Minster, the Saxon Cathedral. It is the oldest item in the exhibition, symbolising the re-founding of the City after the Romans left. As the inscription cut into the plinth says: Winchester’s first cathedral was begun around 650. At its heart stood an altar. This stone formed its base. Here the power of the Church and the King met. The second picture is the three-quarter size replica of the 1476 shrine of St Swithun, with the reliquary for his miracle-working bones on top. Fragments of the shrine that remain, some of which are in the exhibition, were used to determine what the replica should look like.