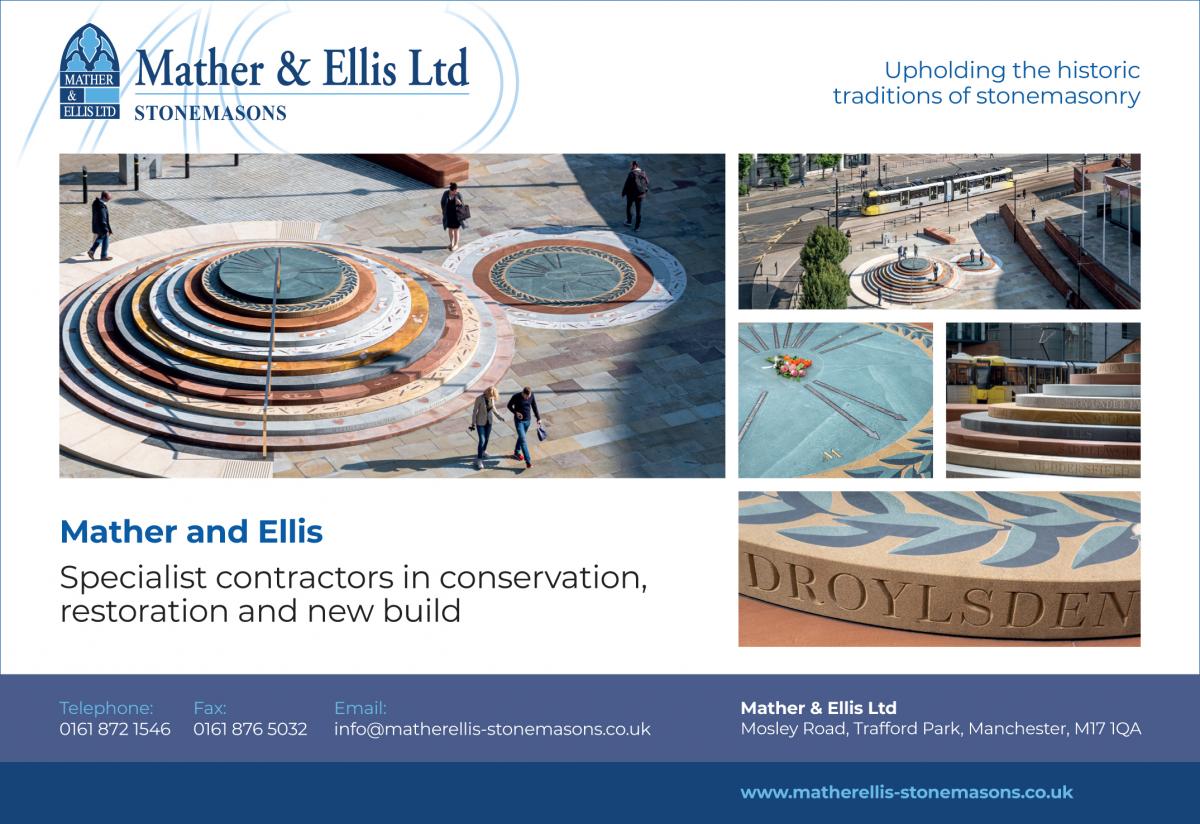

Manchester commemorated the 200th anniversary of an infamous day in its history known as the Peterloo Massacre with a £1million memorial in British stone, built by Manchester stone company Mather & Ellis. It is an outstanding example of masonry skills in British stones.

It has taken 200 years, but there is now a memorial in Manchester to commemorate those who died in the Peterloo Massacre, recorded in Shelley’s poem, The Mask of Anarchy. The massacre saw troops ride into a crowd of 60,000 men, women and children, sabres drawn, killing and injuring hundreds of them.

The memorial was erected by Manchester stone company Mather & Ellis – and what a superb example of stonemasonry craftsmanship and display of British stones it is.

Commissioned by Manchester City Council and designed by Turner prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller, it is part of a scheme by Caruso St John Architects with Conlon Construction as the main contractor.

Mather & Ellis Director John Russell says his involvement began when he was visited by a representative of Conlon in November 2018 and was told the project had to be completed in time for the 200th anniversary of the massacre in August 2019. “At that time they didn’t even have planning,” says John, who accepted the project but admits it gave him sleepless nights. “I wasn’t convinced we could finish in time.”

Conlon Construction was chosen as the main contractor because Manchester has a term contract with the company. Conlon approached Mather & Ellis because it had priced the work for the architect on the project a couple of weeks before. “The only brief we had was that it had to be in indigenous stone,” says John.

Conlon Construction was chosen as the main contractor because Manchester has a term contract with the company. Conlon approached Mather & Ellis because it had priced the work for the architect on the project a couple of weeks before. “The only brief we had was that it had to be in indigenous stone,” says John.

In spite of John’s reservations, the work was actually finished a week ahead of schedule.

Most of the stone was bought as block and worked by Mather & Ellis, although DeLank and Fyfe Glenrock worked the granites they supplied and Burlington worked its Broughton Moor slate that tops the memorial, while DAR Marble & Granite, another long-standing Manchester stone company, used its Denver Quota CNC machine to cut the inlays to the top of the stone treads to accept the inserts, while the inserts were cut on a waterjet by Aquacut in Knutsford, Cheshire. The files for the CNCs to work to were prepared by Mather & Ellis.

There are a lot of inserts in the 19 courses of stone. They include bronze by architectural metalworker Leander Architectural in Derbyshire in the Broughton Moor Cumbrian slate in the centre of the circles. Broughton Moor and Welsh Cwt-y-Bugail slate are used as inlays in Peak Moor sandstone; Cove Red sandstone and DeLank Granite in Whitworth Blue; St Bees red sandstone and Cwt-y-Bugail in DeLank; Corrennie Pink and Dolerite from Scotland in Cop Cragg; Dolerite and Cop Cragg in St Bees; St Bees and Cwt-y-Bugail in Fletcher Bank. They appear in splendid combinations that delight the eye and lift the spirit.

The lettering was cut by hand by the masons of Mather & Ellis – and there’s a lot of it. It includes the names of 18 people who died in the massacre (although many more died of their wounds subsequently) and the places the protesters came from. Laying out of the lettering and producing templates for the masons to work from was carried out by Mather & Ellis using AutoCAD.

The lettering was cut by hand by the masons of Mather & Ellis – and there’s a lot of it. It includes the names of 18 people who died in the massacre (although many more died of their wounds subsequently) and the places the protesters came from. Laying out of the lettering and producing templates for the masons to work from was carried out by Mather & Ellis using AutoCAD.

The monument is 1.8m high and consists of two circular designs, one in the pavement and one rising out of the pavement in diminishing circumference concentric circles on top of each other, creating steps or seats for people to use as a civic space in what Caruso St John describes as the best tradition of Victorian architecture.

But the design brought protests from the time it was announced to the time it was unveiled from people in wheelchairs who objected that they would not be able to access the summit.

But the design brought protests from the time it was announced to the time it was unveiled from people in wheelchairs who objected that they would not be able to access the summit.

Jeremy Deller did amend his design just before it went for planning approval to incorporate a semi-circular ramp of Portland limestone around the base to enable wheelchair access all around the monument, but the problem of reaching the top remained and throughout the construction a dignified demonstration was mounted one evening each week by people in wheelchairs and their supporters.

The controversy denied the memorial the grand opening many believe it richly deserved. Instead, the council simply quietly removed the fencing around it that had protected the site during construction three days before the anniversary of the massacre. There was talk of adding a lift to make the summit accessible to wheelchairs, although that would inevitably compromise Jerry Deller’s artistic concept.

The controversy denied the memorial the grand opening many believe it richly deserved. Instead, the council simply quietly removed the fencing around it that had protected the site during construction three days before the anniversary of the massacre. There was talk of adding a lift to make the summit accessible to wheelchairs, although that would inevitably compromise Jerry Deller’s artistic concept.

Commentary on the accessibility of the memorial joined with Manchester’s ongoing homelessness crisis and references to the financial crash and an Immigration Removal Centre at Yarl’s Wood when the 200th anniversary of the massacre duly arrived and events were held to mark it.

The air of protest was, perhaps, appropriate for what the memorial commemorates, as the original Peterloo demonstration so violently broken up was calling for parliamentary reform and an end to the corn laws that protected the incomes of wealthy land owners by keeping food prices artificially high.

The air of protest was, perhaps, appropriate for what the memorial commemorates, as the original Peterloo demonstration so violently broken up was calling for parliamentary reform and an end to the corn laws that protected the incomes of wealthy land owners by keeping food prices artificially high.

Whether the memorial does eventually get wheelchair access or not, John Russell says he and his team are “absolutely delighted” to have been involved in the project.

Being from Manchester, John says he was aware of the Peterloo Massacre but doubts many people throughout the country were. It is hoped the memorial will help raise the profile of the Peterloo Massacre.

“Every time I pass it there are people looking at it,” says John. “I think a majority of schools in the city have visited it and everyone involved has taken their families to see it. I will be proud to have been involved in it every time I pass by for many years to come.”

“Every time I pass it there are people looking at it,” says John. “I think a majority of schools in the city have visited it and everyone involved has taken their families to see it. I will be proud to have been involved in it every time I pass by for many years to come.”

Inlaid into the Broughton Moor centres of the circles are the Leander Architectural bronze pointers indicating the direction of other state attacks on civilians, including Tiananmen Square in China and Bloody Sunday in Derry.

The reference to the other atrocities gives a wider poignancy to the memorial, because the artist wanted it to carry the message that the case of a state turning against its citizens is not unique to one place or time.

The Mather & Ellis contract included the ground work of paving and a dwarf wall. Two people did that while five masons were on site for the build of the memorial. Six more of the 34 people the company employs were brought in to help with the lettering.

The stonework is built around a reinforced concrete frame. The accurate positioning of each unit was vital, as small errors in setting out a circle can quickly cause problems if the exact perimeter is not followed, resulting in a distorted shape.

Each day John Russell insisted that measurements from the centre-point to the perimeter were double checked, but this proved to be time consuming. The masons on site came up with a solution. They built a wooden jig (pictured on the previous page) that they took spots off for each stone with the help of a laser level. It clearly worked as the finished job is perfect.

John, along with Nigel Sharpehouse and Paul Hilton from Conlon, were pivotal to the project, in conjunction with project architect Elena Balzarini and Paul Henderson and Dave Carty from the council. So there was some consternation when, in the middle of it, John took a previously arranged five-day cycling holiday in Portugal.

He admits he would not ideally have taken a holiday during the build if it had not already been arranged. Concerns were raised about him being injured and not being able to return to work, but fortunately the problem did not arise.

At various points throughout the project Jeremy Deller, who likes to involve others in the creation of his works because he feels it diminishes the artistic ego, visited to see how his vision was being realised. He paid several visits to the Mather & Ellis yard in Trafford Park to see the stones taking shape.

All the stone companies that contributed to the memorial were delighted to have been involved. As Rob Dunkley at DAR says: “We are very, very proud of it and to have been involved in it.”

And Richard Collinson, Commercial Manager of Fyfe Glenrock, which worked the Scottish Corrennie Granite and Whinstone, said: “We were pleased to be able to work on this project and supply not just one material, as per our original brief, but also a second.

“The Corrennie Pink was the first course to be laid. We hit the target deadlines, which resulted in Fyfe Glenrock being asked to add an additional course in Scottish Whinstone.

“Granite and Whinstone have similar properties and both have been widely used in building works for hundreds of years. The contrasting colours of these materials and the others from around the UK that make up the layers creates a striking impression on the finished appearance of the memorial.

“The memorial has been described as both subtle and powerful and it’s fitting that there is a visual symbol to remember the price paid for democratic representation.”

The companies that supplied the stones were as follows:

Blockstone: Peak Moor; Cove Red

Burlington: Broughton Moor

DeLank: DeLank granite

Dunhouse: Cop Crag

Fyfe Glenrock: Corrennie Pink granite

Marshalls: Whitworth Blue; Fletcher Bank

E Moorhouse & Sons: St Bees

Portland Stone Firms: Portland

Tradstocks: Whinstone (Scottish Dolerite)

Welsh Slate: Cwt-y-Bugail

Jennifer Rhodes, Secretary of The Lancashire Group of the Geologists’ Association (https://geolancashire.org.uk/) kindly sent us the PDF you can download below. She said:

This is the document I made for the GA Conference in October of last year. It was held at the University of Manchester on the weekend of 18/19/20 October.

We ran four field excursions including a Manchester Building stones walk, which suited people who had trains to catch back to the South East. I began at the Peterloo Memorial, which had been opened on 16 August, the 200th anniversary of the massacre, as you say. Everyone enjoyed the walk (or so they said!) but, of course, by the time I got to the Crown Court building at the end of the tour we were a very small band of brothers, most people having taken off to catch their trains. I made the attached document so that those people who left were able to read about what they had missed - and might perhaps come back for another walk. I hope others will enjoy reading it.