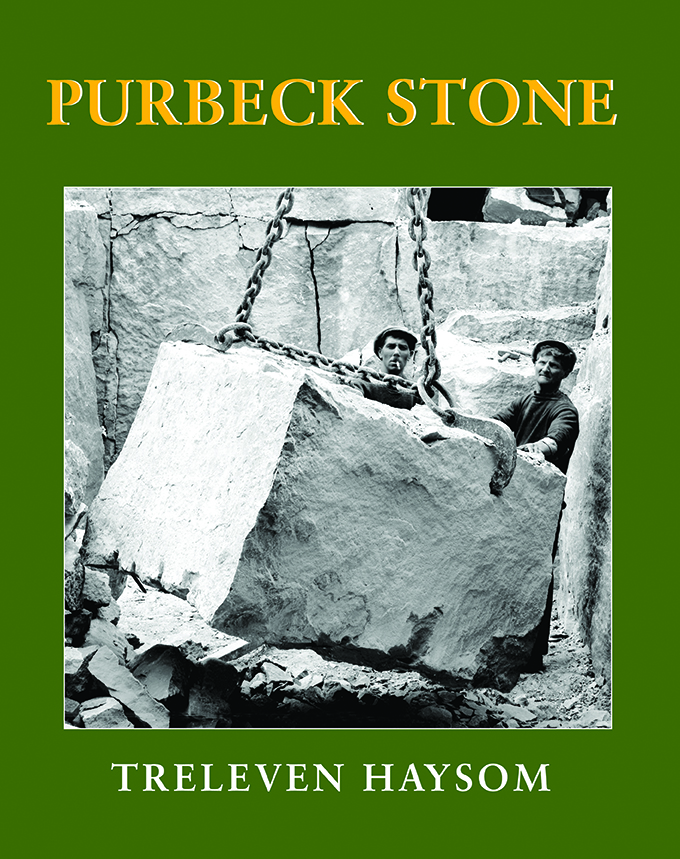

Published by The Dovecot Press

Author: Treleven Haysom

ISBN: 978-0-9955462-264

Pages: 312

Illustrations: More than 350

Price: £35

To buy a copy, click here.

Treleven (Trev) Haysom is steeped in the traditions of Purbeck quarries and the limestone that comes from them. He grew up playing in the quarries his family had worked since the 17th century and counts himself lucky to have been brought up in an age before ‘helicopter’ and ‘stealth fighter’ parents monitored every action of their offspring. “My father’s approach to us children mucking about in the quarry was ‘keep out of the way’,” he says in the introduction to his book published last month (October) called, simply, Purbeck Stone.

The title is all encompassing of this particular subject – and so is the book. At around 220,000 words in 312 pages with more than 350 illustrations it covers every aspect of the stone – although that should really be in the plural because each bed of Purbeck has its own characteristics and nature, as Trev explains.

It has been 18 years since Trev was commissioned to write Purbeck Stone, although really it is a lifetime’s work... in fact, even more than that as it draws on the experiences and records of generations of the Haysom family who have worked in the quarries of the Dorset island of Purbeck.

Where to start? The obvious answer is at the beginning. But, to be honest, it is going to take someone particularly dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge about Purbeck limestone and its extraction to read this book from start to finish.

One of the photographs from Trev’s book is the Bankes Arms in Corfe Castle village, with its mid-20th century example of a graduated Purbeck stone roof, with the largest courses at the bottom and the smallest at the ridge.

One of the photographs from Trev’s book is the Bankes Arms in Corfe Castle village, with its mid-20th century example of a graduated Purbeck stone roof, with the largest courses at the bottom and the smallest at the ridge.

It is more likely to be a book that people will dip into from time to time and refer to whenever they want to check something about the stone industry on Purbeck – and it has a pretty comprehensive 10-page index to facilitate that, as well as eight pages of notes, a bibliography, and an 11-page glossary to explain the terms used in the Purbeck stone industry.

Treleven Haysom’s practical experience gained from a lifetime of quarrying and masonry work transforms the bare bones of the industry’s history into a story enriched by oral and working traditions handed down through the generations by his family and the people they have worked with.

Trev probably knows more about Purbeck stone and the traditions that go along with extracting and using it than any other living person – possibly more than anyone who has ever lived. He has served as Warden of The Company of Purbeck Marblers & Stonecutters and in 2014 was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Bournemouth University as an authority on the stone beds and the fossil records within them. A mammal from the Cretaceous identified from a tooth found on Purbeck has been named Dorsetodon Haysomi in recognition of his contribution.

He has laid out a lot of his knowledge in this book, making it an important historical record that deserves a place in the archives of the stone industry, Purbeck and the British Isles.

Purbeck quarrying in the mid 20th century. This is Bonfield’s quarry. A cart, hidden by its load of stone, is being lowered over the roll stone at the top of the slide. The horse that can be seen is turning the capstan to lower the cart.

Purbeck quarrying in the mid 20th century. This is Bonfield’s quarry. A cart, hidden by its load of stone, is being lowered over the roll stone at the top of the slide. The horse that can be seen is turning the capstan to lower the cart.

Because there is such a long history of winning stone on Purbeck there are also some intriguing, even exciting, stories, including those from the Purbeck Marblers archives involving the illegal selling of quarries and avoidance of royalties going back to the Civil War of the 17th century.

The information is densely packed in, with a lot of historical references and quotations to pick through and even a host of new words to come to terms with. It is not a light read, but it provides a fascinating and intriguing insight to the historical workings and relevance of an industry that is rapidly changing in the face of evolving technology and working practices.

Although The Dovecot Press says it has taken a long time to write this book because they commissioned it from Trev 18 years ago, it actually started to take shape as long ago as the 1960s. As Trev explains in his introduction, he had been bird watching in Dungeness in Kent and visited a church in Winchelsea. The guide book described some medieval monuments as being in Sussex stone, but Trev said they were Purbeck stone. From then on, he started recording Purbeck stone wherever he came across it and this book records some of the many examples he has found, illustrating how the different beds of the stone from Purbeck have been used.

The book begins with an explanation of Purbeck stone, and the distinctly different beds that have resulted from the changing conditions in which they were laid down over geological time.

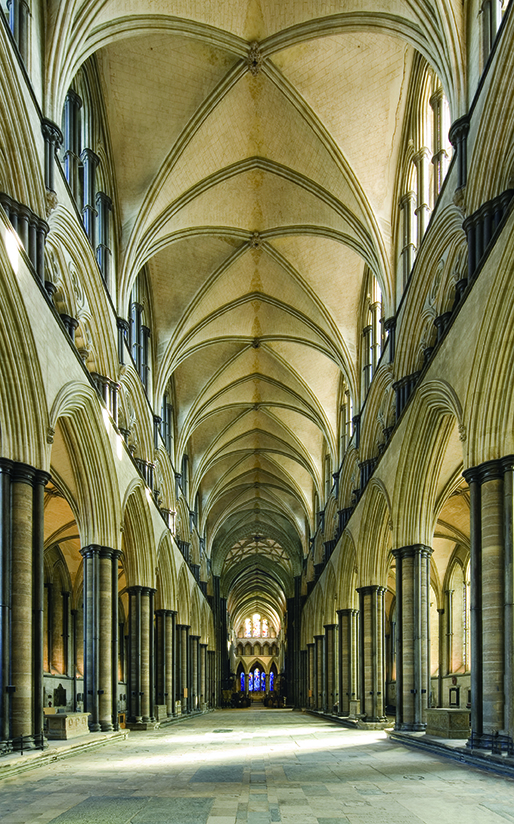

Purbeck Marble, highly valued and used in various cathedrals, churches and stately homes, is among the beds that gets a chapter to itself. Trev explains: “The high point [of its use] can perhaps be identified in Henry III’s lavish use of marble in his rebuilding of Westminster Abbey in about 1245, complete with Cosmati pavement and Confessor’s shrine, where more exotic types of stone are set in Purbeck marble.”

He explains how the marble was used for coffins and tombs, and says: “Other rarer usages include the wonderful 12th century screen from Southwick Priory, Hants (removed and in the care of English Heritage), the fountain at Westminster (its flower-like form is, it seems, unique, but how many other abbeys may have possessed such fountains?), St Augustine’s chair in Canterbury, the great table in Westminster Hall and components in some of the Eleanor Crosses, all 13th century.”

Another chapter is devoted to Cliff Stone, which includes the Portland group of rocks that take their name from another of Dorset’s islands where they are prominent. This chapter has one of the huge number of throw away gems that are a significant part of the delight of Treleven’s book and make it an ideal present for anyone interested in stone, building and history in general.

“Billy Winspit puts his ‘Top Mast’ as the small quarry high on the east side of the cove at the east end of Hedbury. He provided the information for the Anderson Map of 1962, which has been much reproduced. One or two names are in the wrong place, but as Dr Anderson remarked, it would have been a miracle for it to be entirely accurate considering how much whisky was drunk by the toponymist during its preparation.”

Elsewhere, the danger of quarrying is also recorded. “Thomas Collins told me of the death of his grandfather, Frederick John Harris, who ‘was accidentally killed at the quarry’ in 1888. It was caused by the sudden failure of an unnoticed weak vent in a block of Cap they were moving. He was 69.”

There are several other gruesome stories, including a man who lost his arm after a half-ton rock fell on it. He was pinned down for four hours before he managed to pull himself free.

Below. Salisbury Cathedral nave, showing the use of Purbeck Marble in the arcade, triforium and clerestory.