Scan this QR code and press ‘search’ to see a 3D model of Doddington Hall created by AH Scanning. It is low resolution to speed up the download.

Architectural & Heritage Scanning is a new company offering scanning without scaffolding. And it is run by people from the stone industry who understand what they are looking at.

While the digital templaters of companies such as Prodim and Laser Products have significantly improved productivity for many companies in the hard surfaces worktop sector, this is only the tip of the iceberg of what can be (and is being) achieved with digital plotting.

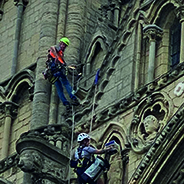

Digital surveying and 3D scanning are now making inroads into all kinds of building surveys, especially in conjunction with drones and roped access for high level surveying without scaffolding.

A start-up from the stone industry offering this service is Architectural & Heritage Scanning, which has offices in Stamford and Milton Keynes. It was incorporated last year by Henry Flint (who works at Ketton Stone) in conjunction with Graham Sykes, an architectural designer of 15 years who worked alongside Andy Maclean at Stewart Design, specialising in stone projects.

Ketton Stone might be best known for its traditional new build work on load-bearing stone structures, but it is perfectly happy to use digital technology when it comes to working the stone as long as it does not compromise the quality of the work.

And digital surveying is anything but a compromise. It can produce a scan that is dimensionally precise and sub-millimetre accurate. The information gathered can be used for CAD (computer-aided design) and output as DXF files for use on a CNC machine, such as a saw or waterjet cutter, to produce masonry that needs no further work onsite.

Henry had become used to using hand-held scanners to record heritage stonework accurately for reproduction and to scan artists’ maquettes to scale up and produce in stone, while Graham had been doing a lot of point cloud scanning of façades. Joining the two skill sets together produced a result greater than the sum of its parts, especially taken in conjunction with their knowledge of stonemasonry and in-house abseiling skills. It means they can get up close to the stone if they need to and understand what they are looking at.

They believe that gives them a proposition that has a lot to commend it to the rest of the stone industry and on that basis they decided it was worth investing heavily in drones, laser scanners and photography equipment, and getting out there with the offer.

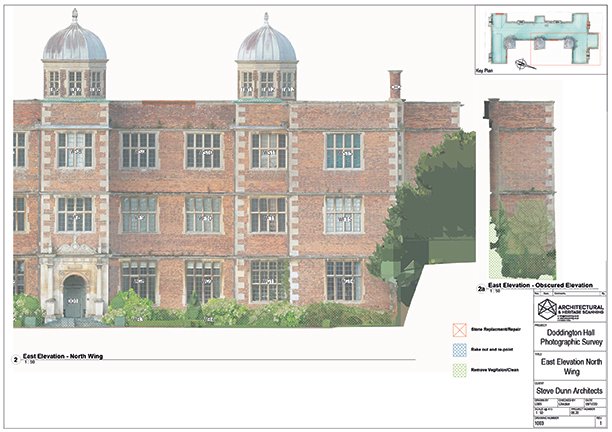

Not that digital surveying and scanning is just about accuracy. It is also quick and non-invasive. One of the buildings they surveyed was Doddington Hall, an Elizabethan manor house in Lincolnshire, for Steven Dunn Architects.

Not that digital surveying and scanning is just about accuracy. It is also quick and non-invasive. One of the buildings they surveyed was Doddington Hall, an Elizabethan manor house in Lincolnshire, for Steven Dunn Architects.

The architects say: “Graham and his team at AH scanning have been actively engaged in all of the scanning work undertaken at Doddington Hall and the information provided has enabled them to prepare our tender documents in a far more informed and accurate way than has been possible previously using traditional measurement techniques.

“When there is the need to establish highly accurate, measured/scalable information (masonry sections, window openings, defective areas, and so on) at an early stage in the development of the project, then there is simply no substitute for this technology.”

The survey linked together 2,500 photographs with a highly accurate point cloud scan rectified to form a complete 3D picture of the whole building – scan the QR code (right) to see a low resolution version to get an idea. It also produces orthographic (2D) projections of individual façades for use with computer-aided design (CAD).

When viewing a 3D scan of a façade it is possible to zoom in close to inspect individual stones. If the interiors have also been scanned, you can even go through the walls and see inside.

The alternative might be to put up scaffolding and then carry out a visual survey. To cut out a stone and take moulding details from it to reproduce would take a mason four times longer than doing it using a scan. And by using a scan from a drone or rope access, the replacement stone can be produced before any intervention impacts the building. It might even be possible to replace the stone using roped access.

For many heritage buildings, scaffolding is not just an expense, it also means a loss of revenue because visitors either choose to stay away because they want to see the building and can’t when it is covered in scaffold, or the venue has to be closed for the health & safety of all concerned.

While the scanners are important, they are no good without computers to interpret the scans – and the amount of data to be processed can be significant.

The idea of using photographs for surveying is not new. Photogrammetry dates back to the early days of photography in the 19th century. It moved on a lot during World War I, when it was used in conjunction with aeroplanes to create maps of the enemy lines and communication channels. But it was, of course, all analogue and required significant skills to make and use the equipment, which meant it was expensive.

As we move deeper into the digital age the equipment has become less expensive and the use of it requires different skills – a process of change that continues. Analogue film can contain a huge amount of information in a relatively small space. Getting close to that level of detail with digital technology requires a lot of memory and a lot of processing power to make the use of the information acceptable.

Architectural & Heritage Scanning surveyed Peterborough Cathedral using point cloud. The scanner takes readings at 120million points a minute. The final 3D file was 1.1terrabites and contained 20billion data points. Graham: “It’s been a challenge to take these really large data sets and manipulate them so people can use them.”

To deal with the processing of such large files, Architectural & Heritage Scanning commissioned custom built PCs – in fact they have four of them. Part of what they do on them is transform the data they collect into formats of a manageable size that customers can use on their own tablets, laptops and smartphones, which helps with getting approval for projects without having to have a site meeting.

There are some architects who can use point cloud data, and Architectural & Heritage Scanning are happy to supply it when it is requested. Most, though, cannot use it and need information in a form they can use with their usual CAD programmes, such as AutoCAD.

Sometimes, using the data can involve the customer linking back to the Architectural & Heritage Scanning computer using TrueView software, which produces a result similar to Google’s StreetView but with measurements, so it can be used as a scale drawing. The link is via the internet using a customer specific URL to keep the data secure.

The technology does not have to be used for façades or whole buildings. Architectural & Heritage Scanning have lately scanned a bathroom. The dimensionally correct data have been used to cut all the horizontal and vertical stonework needed for the project without the company producing it ever seeing the building it will be going into except on a screen and as CAD drawings produced from the scans.

You might say you could do the same with digital templaters, but Graham says in the time it takes to make 50 measurements using digital templaters a scanner will have taken millions of measurements. “We get in quickly and unobtrusively and cull a lot of information,” he says.

There is a lot of talk these days of creating ‘digital twins’ of buildings, although Graham questions just how much of a twin some of them actually are. “Our scans really are digital twins,” he says, “because they are very, very accurate and contain a huge amount of dimensional data as well as high resolution visuals.”

And they can be used with BIM (building information management) workflow. Architectural & Heritage Scanning use Revit software to create highly accurate BIM models from the scan data collected.

In January, Architectural & Heritage Scanning had 18 live projects. The largest Graham and Henry have worked on to date was a £15million renovation. Sometimes their surveys even produce revelations – for example, their scans discovered Peterborough Cathedral’s towers lean out a little, which nobody had noticed previously.

Roped access is just one of the tools in the armoury of Architectural Heritage & Scanning.