In medieval England, Purbeck Marble was widely used to decorate important buildings. Now English Heritage has published a new guide on how to preserve what remains of it.

Following a webinar on looking after Purbeck Marble last year, Historic England has this year published a Technical Advice Note on the conservation and repair of Purbeck Marble in its Looking After Historic Buildings series.

Compiled by David Odgers, Clara Willett and Alison Henry, Purbeck Marble: Conservation and Repair, sums up in 68 pages how Purbeck Marble has been used, how it has decayed over the years and how to conserve what remains.

This is not a publication that competes in any way with Treleven Haysom’s 300-plus page weighty Purbeck Stone tome published last year (see review in NSS November 2020), not least because it focuses on just one of the 20-or-so named beds of stone extracted from the Dorset island of Purbeck.

Trev’s book does have a chapter on Purbeck Marble but, if anything, the Historic England publication can be seen as a complement to it. And Treleven Haysom is among the contributors to the Historic England publication.

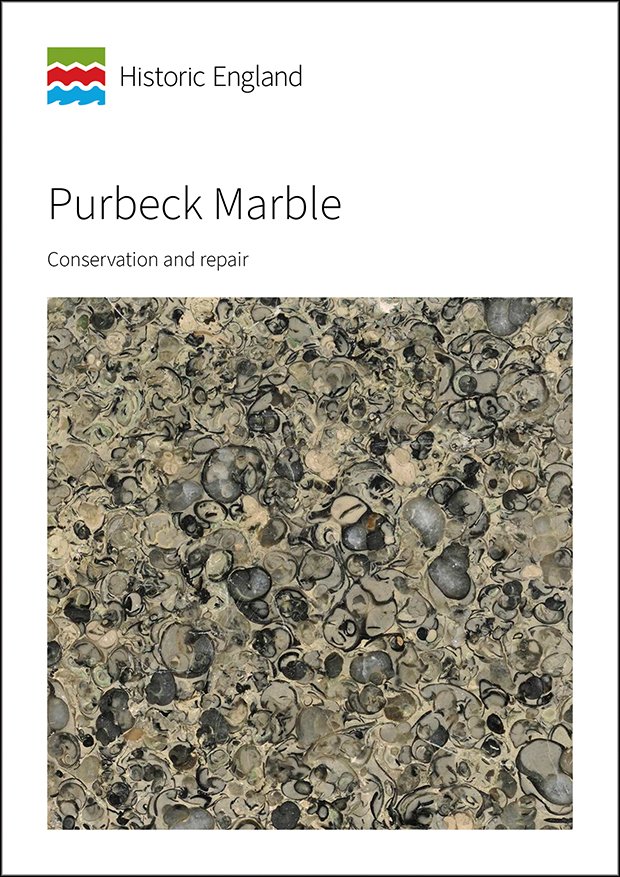

Purbeck Marble is not what a geologist would call marble because it has not undergone the metamorphosis created by heat and pressure in the earth’s crust that signifies a true marble. It is simply a hard, polishable limestone, although that was enough to earn it the title of being a marble in its medieval heyday between the 12th and 16th centuries and why those who quarried and worked it were called ‘marblers’ and those involved in the stone industry on Purbeck formed the Company of Purbeck Marblers & Stonecutters.

For medieval builders, Purbeck Marble had many advantages. Not only was it hard, colourful, interestingly textured, easily polished and cheaper than true metamorphic marble, almost all of which was imported, the quarries were also close to the sea. This meant the stone could be transported around the coast and along rivers. Mostly it was used in England, but occasionally it was taken further afield (notably, to Normandy).

Although Purbeck Marble was cheaper than Italian marbles and others from further afield, it was still more expensive than most British stone and tended to be used to decorate rather than build with, although cathedrals (in particular) do have architectural masonry, mouldings and flooring in Purbeck Marble. And the Grade I listed town cellars in Poole, Dorset, are built of Purbeck Marble.

Purbeck Marble: Conservation and Repair lists the main uses for Purbeck Marble as:

- Architectural elements

- Fonts

- Effigies

- Tombs

- Ledgers, coffin or tomb lids

- Floors

As well as enhancing the figurative nature of the stone, polishing was the traditional way of preventing decay in marble.

In the Historic England publication it says: “As early as AD77, Pliny the Elder advocated this method as a protective measure. While polishing alone will not completely prevent or stop decay, it plays an essential role in protecting both Purbeck and ‘true’ marble. This is because polishing closes the pores of the stone, which helps to minimise water penetration. Rough surfaces also have a greater surface area than smooth ones of the same dimensions. Polishing the stone will reduce the area that is exposed to moisture.”

And, of course, moisture is the enemy of all stone – and just about any other material – and especially limestone when the water contains sulphates that turn it acidic, because limestone (and true marble, which also consists of carbonates) dissolves in acid.

Historic England points out that Purbeck Marble was often treated to protect it. It says: “The regular treatment of Purbeck Marble with natural waxes, oils and resins was assumed to be beneficial to the stone’s long-term preservation. Unfortunately, although these treatments provide some protection, they may also cause aesthetic changes and a reduction in permeability.

“The darkening of surface treatments, especially from the cross-linking of polymers contained in these materials, will turn the original grey/green of Purbeck Marble to dark brown. These surface treatments also become brittle with age, leading to micro cracking. When this happens, moisture can penetrate behind the coating and set off humidity-driven decay mechanisms, causing the surface to blister and take on a milky appearance. The ‘tackiness’ of waxed surfaces can also attract dust, dirt and pollution, which may change the original colour of the stone.”

Although there have been many attempts to restore the polish of Purbeck Marble, most of the specific ingredients used in past treatments have been unrecorded.

Historic England: “Architect Bernard Fielden’s intervention on the Walter de Gray tomb and other Purbeck Marble in the 1970s at York Minster is an exception. Fielden’s method consisted of stripping surface treatments with dichloromethane paint remover, rubbing down the stone with ‘cream grit’ and then ‘snake stone’, and finally polishing it with putty powder (containing tin oxide) and oxalic acid crystals.”

Unfortunately, the formulation for ‘cream grit’ and ‘snake stone’ seems to be lost. If anyone knows what was in these products, Historic England would be delighted to hear from you - email conservation@historicengland.org.uk.

Purbeck Marble: Conservation and Repair continues: “This approach was broadly successful in that the lustre and appearance of the Purbeck Marble were restored and still remain intact (The Sir Bernard Fielden Archives, York Minster Archives).”

The publication itemises some of the forms of decay in Purbeck Marble:

3.3 Oxidation

Purbeck Marble contains the mineral pyrite. When the relative humidity exceeds 60%, pyrite oxidises to form ferrous sulphate and sulphuric acid. The extent of this oxidation is usually apparent from the way in which the surface of the Purbeck Marble discolours to brown. The sulphuric acid also reacts with the calcite binder in the stone to form gypsum. This not only leads to loss of binder but also disrupts the surface, as it is an expansive reaction.

3.4 Sulphation

Purbeck Marble has a predominantly calcitic matrix. When sulphur dioxide (from general pollution) mixes with moisture and settles on the surface, sulphurous acid is formed, which then reacts with the calcite to form gypsum. Gypsum is 200 times more soluble than calcite. If Purbeck Marble is repeatedly wetted by direct rainfall, the gypsum will usually wash off as it is formed and will not accumulate on the surface. This will cause erosion of the surface. If, however, the stone is protected from direct rainfall but is subject to condensation, the sulphate will form a surface crust that tends to darken and blister. This crust can also affect the moisture-transfer characteristics of the surface.

3.5 Salt crystallisation

Despite the limited porosity of Purbeck Marble, dissolution, migration and re-crystallisation of soluble salts can contribute to its decay. Sources of salts can naturally occur in the stone itself, derive from groundwater, result from applied treatments such as cements, or accumulate from de-icing salts put down on roads and pavements.

Historic England looks at some of the remedies used over time. Architect Sir George Gilbert Scott, for example, described one in 1855 when he was trying to repair the Purbeck Marble of the royal tombs in the sanctuary at Westminster Abbey.

Scott wrote: “I wish to cement together the disintegrating particles as both to prevent them from coming away and also to exclude the humidity which causes the decay. For this therefore I make a weak solution of white shellac in spirits of wine [ethyl alcohol, later replaced with methylated spirits as a cheaper alternative]; this I inject by means of a gardener’s syringe the end of which is perforated with numerous holes so small that jets of water have not force enough to wash away the loose particles of stone. The weak solution soaks in as far as the decay has proceeded and the resinous matter is deposited six times with a day’s interval to each for drying. The last injection is stronger than the others – the necessity for penetration being less. I find that the process secures the loose particles and hardens the decayed stone and I have no doubt will effectually arrest the decay. Such parts as have scaled off are firmly re-attached by strong shellac cement.” (From Jordan 1980).

Historic England says: “This ‘induration’ proved highly successful in reducing ongoing decay: the shellac remains in place, although there is some localised blistering. It is less successful in aesthetic terms, though, as the surface colour has changed from the green/blue hue of the original Purbeck Marble to a deep chocolate brown.

“Many other materials have been used with varying degrees of success. Attempts in the 1970s to consolidate and protect the surface of the decayed Purbeck Marble at the church in West Walton, near King’s Lynn, with polyurethane varnish resulted in failure, the surface yellowing and flaking in both external and internal locations.

“Another recommended treatment, used in the 1990s, was a mix of cosmolloid wax, ketone ‘N’ resin and white spirit. There has been no evaluation of its success.”

Purbeck Marble: Conservation and Repair offers advice on identifying the causes of decay and presents a coherent strategy for the effective maintenance and repair of Purbeck Marble. It would be a valuable publication for any practice or stone company involved in conservation that might involve Purbeck marble. It can be downloaded free from the Historic England website at bit.ly/HEpurbeck.

The web page also includes a link to a recording of last year’s webinar about Purbeck Marble and other publications offering advice on maintaining and restoring historic buildings.

A 14th-century Purbeck Marble memorial ledger slab to Elias of Beckingham (died about 1307) at Holy Trinity Church, Bottisham, Cambridgeshire. Photo: ©David Robarts

Significant deterioration to the Purbeck Marble at Netley Abbey, Hampshire, believed to be due to exposure to pollution from downwind of the site. The deposition of sulphur dioxide combined with water run-off has dissolved the calcite binder of the stone. Photo: ©David Odgers Conservation Ltd