The growth of the stone market in the UK

Updated: June 2023

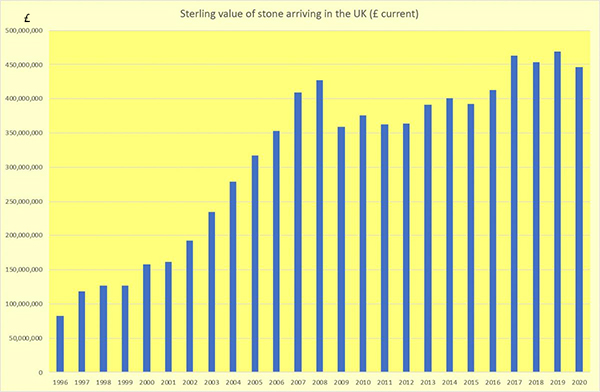

Although stone companies reported some of the heat leaving the market at the end of 2022 and the start of 2023 as the cost of living crisis started to bite, figures from HM Revenue & Customs, based on tax returns, show that the effects of Covid and Brexit have been little more than a blip in the longer term growth of stone, even if it did not always feel like it at the time.

Government interventions avoided what could have been catastrophic effects of the lockdowns in 2020, although quantitative easing (printing money) to pump into the economy contributed to inflation at over 10% in the first half of 2023. The Bank of England addressed this with consecutive rises in interest rates from December 2021. In June 2023 the base rate was 4.5% with more increases looking likely. The Government’s fiscal policy has also kept taxes high.

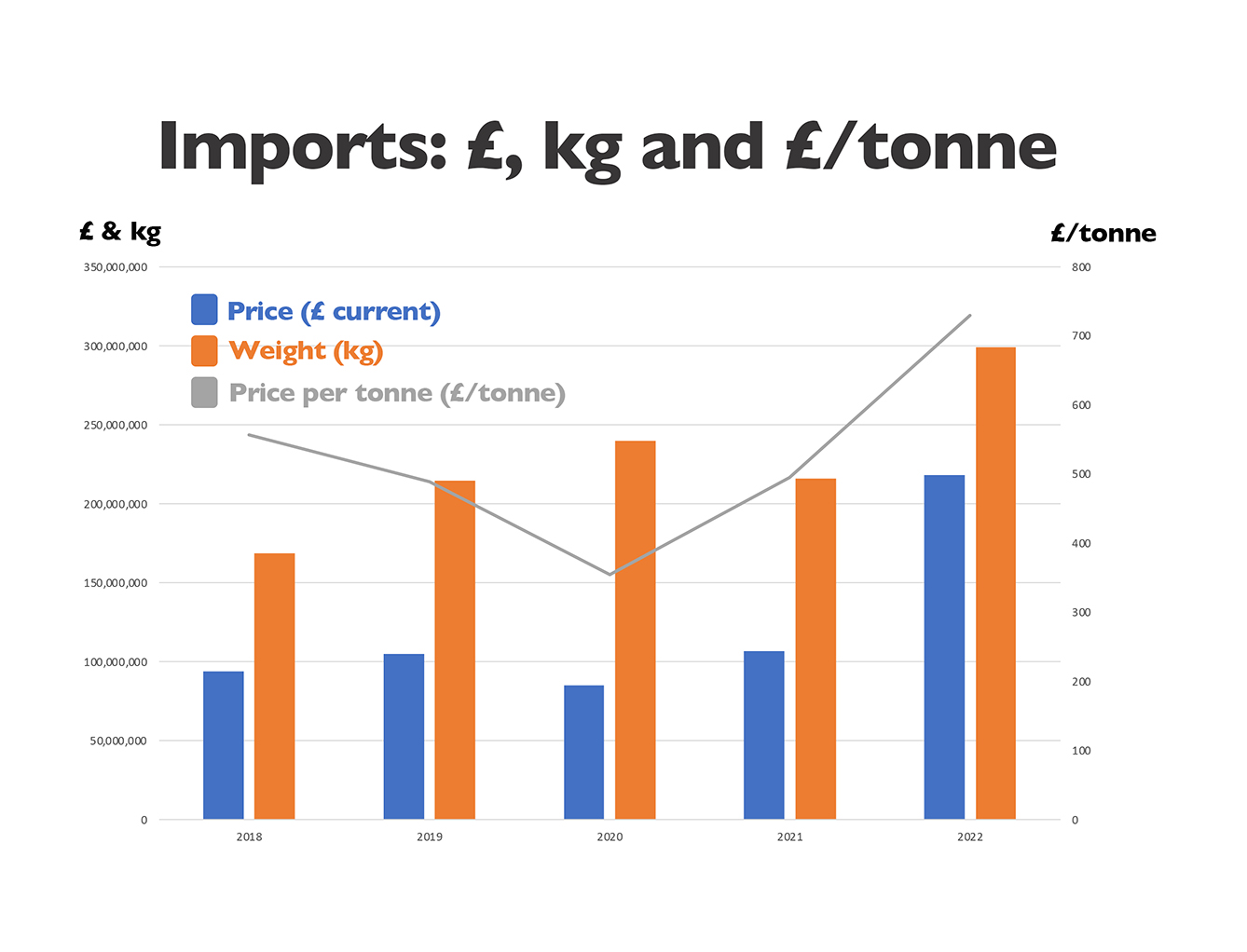

The graphs below, compiled using figures from HM Revenue & Customs tax returns and the Bank of England, tell the story of the rising prices of stone coming into the UK (and 70-80% of the stone used in the UK each year is normally imported) after the fall in prices that accompanied the initial Covid lockdowns.

Sterling price of stone per tonne imported

The total volume of stone coming into the UK in 2020 did not fall, largely because a lot of it comes from China and India and was already on the sea when the seriousness of the pandemic became apparent. It had to be landed in the UK, which presented a problem to importers of where to store it, because sales in the UK dried up for a month or so until the government clarified the position and it became apparent it was possible to carry on working with social distancing.

The value of the stone fell, but lockdowns in China and India and difficulties of shipping quickly saw prices rising again.

There is not a straight correlation between prices and volumes of stone because there is not a single price for stone. It is anything but a commodity. It varies a lot depending on which stone is being bought and for what purposes. Nevertheless, the overall picture told by the graphs above is reflected in the experiences of stone companies.

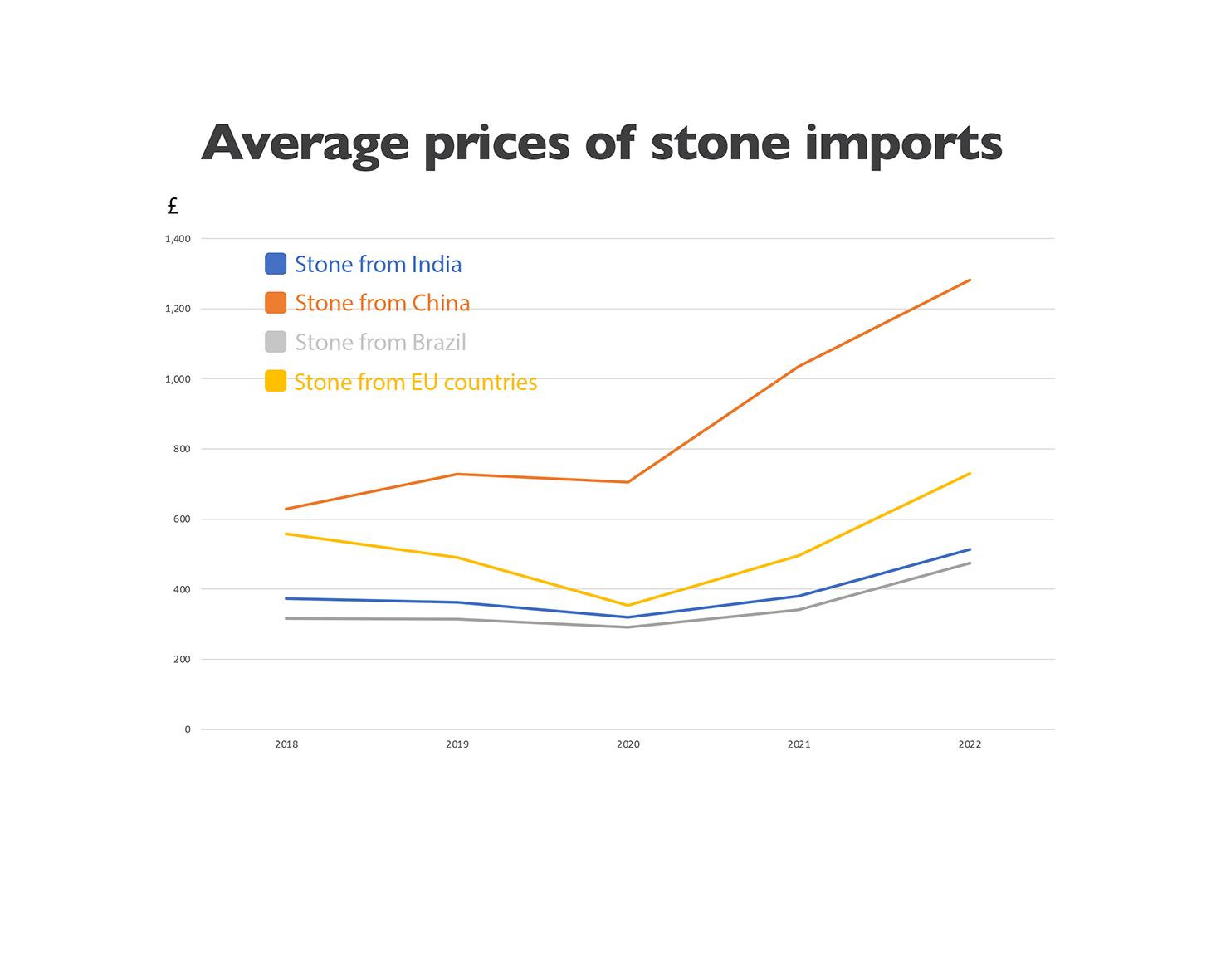

Since Brexit there has, perhaps ironically, been more stone coming from Europe as the prices of getting it from China and India have increased and because of the uncertainty of getting it from Asia when customers want it quickly.

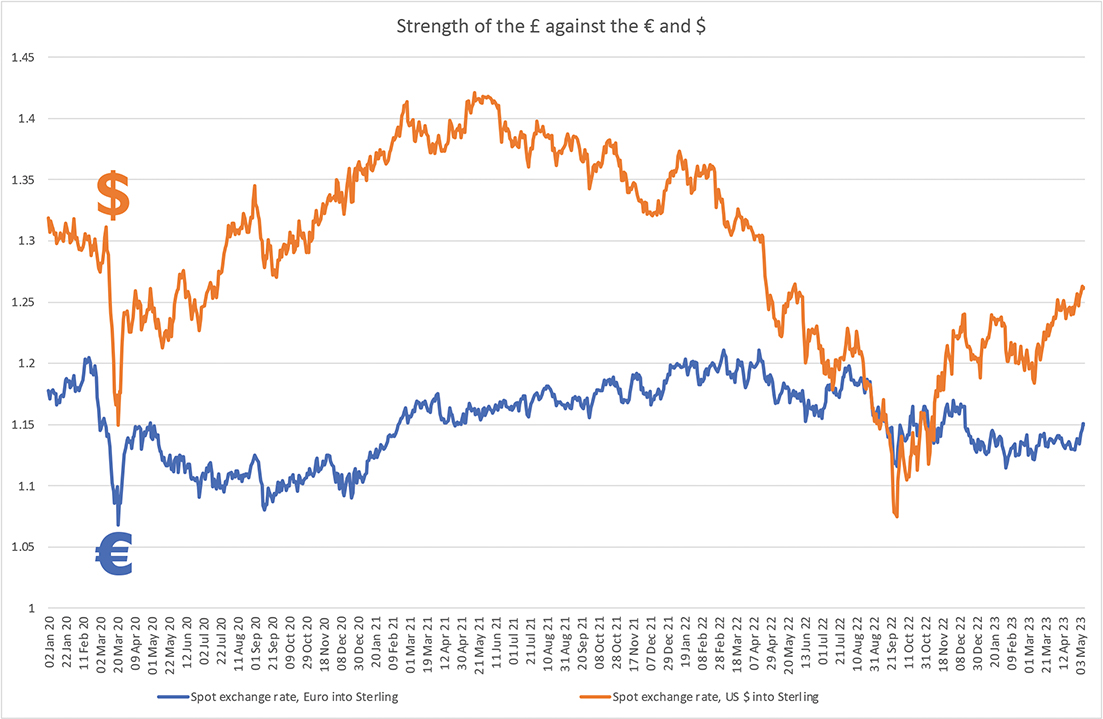

Exchange rates contributed to the price increases, especially of products priced in US dollars (as many imports from outside Europe are) as the dollar strengthened against sterling. The dollar exchange rate has been down and up again since then but prices tend to rise more quickly than they fall.

That has also been true of the costs of fuel and energy, which have played their part in rising input prices for manufacturers.

On the other hand, people are still spending more time at home, with laws proposed to make it easier for employees to get more flexible working arrangements. People who spend more time at home tend to spend more on home improvements such as kitchens and bathrooms and their gardens.

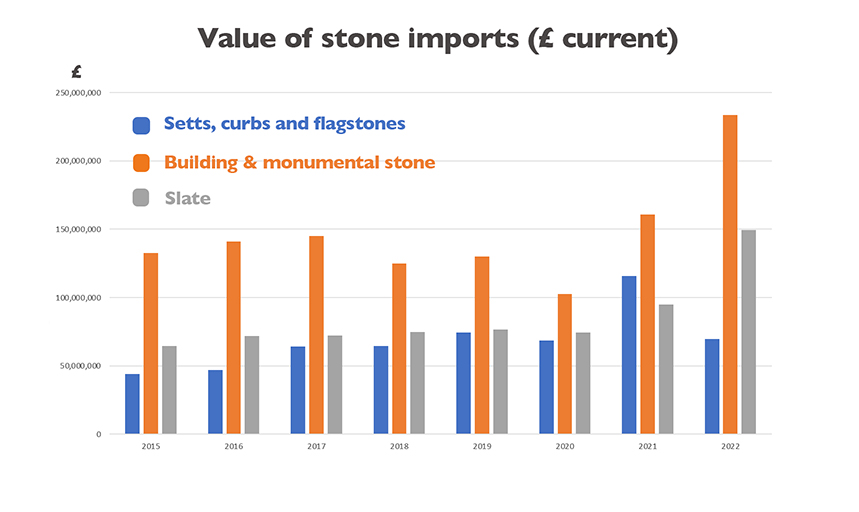

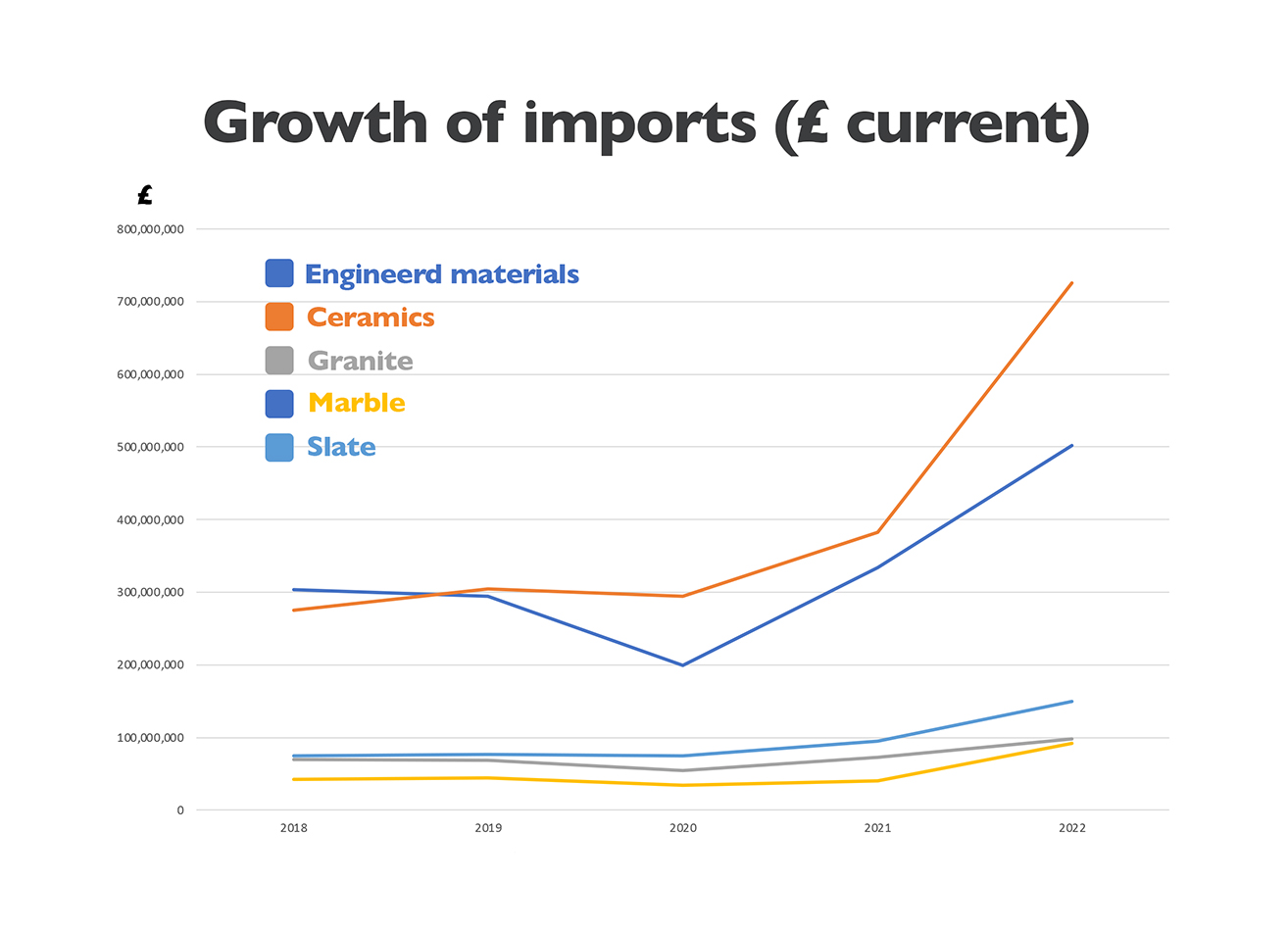

The graph showing the value of different materials imported includes engineered stone and ceramics. Although HMRC’s definitions of product categories is wider than the stone industry’s (especially for ceramics/porcelains/sintered stones), it comes as no surprise that the value of imports is growing, both because prices have risen and because demand has increased.

There are no official figures produced for the production of dimensional stone in the UK nor how it is used, but many of the quarries, especially those supplying paving and walling stone for hard landscaping and housing, have reported healthy demand for their stones. British stone is also used extensively in the heritage sector, which has remained buoyant thanks to support channeled through Historic England and the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Generally, stone companies across the industry have been busy, including those in the memorial masonry sector.

With deaths in 2020 at over 600,000 in England & Wales alone, nearly 14% above the five-year average to 2019, there were more funerals and more stone memorials. In 2021 the death rate was still just over 10% up on the five-year average. Almost all stone memorials installed in the UK come from China or India.

The fact that people could still afford home improvements and memorials was in no small measure a result of the government’s interventions.

Three tranches of quantitative easing in 2020 put an extra £450billion into the economy on top of other government borrowing, the level of which (as a proportion of GDP) has only ever been exceeded during the two 20th century world wars.

And, unlike the credit crunch of 2008 when quantitative easing was used to bail out the banks and resulted in a recession, this time the money was directed into the wider economy and particularly to business – because, in the end, industry pays for everything, through dividends, taxes or salaries.

More than 50 schemes from Westminster and the UK’s devolved governments were put in place to help firms and employees in the UK during the pandemic, with many stone companies making the most of the ‘free’ money (interest free, at least, for the first 18 months) from government-backed loans that suddenly became available to them. Many used the money to prepare for the future by investing in new machinery and technology, and improving their premises.

There were £70billion spent on the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme alone (the CJRS, or furlough). It was paid to 12million people – that’s a third of the UK’s workforce. It is estimated as many as 8million of them would otherwise have become unemployed and who knows how many firms would have gone bust.

Another £80billion went directly to companies through the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS), Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CLBILS), and the Bounce Back Loan Scheme (BBLS). These gave companies loans that were at first interest free, and even when interest had to start to be paid it was usually at only 2-5%.

In addition, more than £25billion was paid out to almost 3million self-employed people in the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS). Construction had the highest number of claims, including 284,000 for the fifth and final SEISS grant. Construction is the largest sector among the self-employed population with 1.2million individuals assessed for eligibility.

There was also all that regional and local authority support, as well as sector specific grants like those from Historic England and the National Lottery Heritage Fund, some of which helped stone companies working in these sectors, not just keeping projects live but also expanding them thanks to the extra cash suddenly available.

The final incentive, encouraging firms to invest now rather than waiting, came in the Spring Budget of 2021 with the so-called ‘super deduction’ on capital allowances. This measure temporarily (it lasted to the end of March 2023) increased relief for expenditure on plant and machinery. It means that investment in plant and machinery qualifies for an allowance of 130%. Ordinarily, it would qualify for the 18% main rate writing down allowance.

So if you bought a machine for £100,000, this increases to 130% (£130,000) and the deduction against tax is £24,700. Without the ‘super deduction’ the standard allowance would have been £19,000. The company can, therefore, make an additional claim of £5,700 against its tax liability.

There was a slight sting in the tail in that when the super deduction ended in 2023, Corporation Tax increased from 19% to 25%, as the government tried to find ways to pay off debts of just over £2.2trillion – about 100% of GDP.

With so much extra money in the economy it is not surprising demand remained strong. But there were difficulties getting products through the docks as a result of both Brexit and Covid, and a shortage of lorry drivers to deliver those goods that did get through, with 15,000 drivers having returned to their home countries, either because of Brexit or Covid, and thousands of HGV tests having been postponed because of Covid.

There have been other skills shortages as well, not least in construction, and when demand exceeds supply the predictable result is price increases, hence consumer inflation reached double digits in 2022, especially with the Russian invasion of Ukraine resulting in an upward pressure on already rising fuel prices.

To try to control inflation, the Bank of England increased interest rates. That makes borrowing more expensive – for the government as well as firms and individuals. With any luck, the high levels of investment in machinery and equipment by companies in 2020-22 will improve Britain’s strangely sluggish productivity, so paying off the debt will be a bit less painful.

Understandably, the value of stone arriving in the UK took a dive as a result of the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020. Nobody was quite sure what was allowed and what was not, including the government. This was, after all, a novel experience for us all.

Many building sites and companies throughout the construction industry closed down. However, the government then made it clear construction work could continue and most of it resumed after a five-to-eight-week shut down.

As mentioned above, there was a bit of a lag between the start of the first lockdown towards the end of March and the fall in the amount of stone arriving at the docks due to amount that was already on the seas. But by the end of 2020, stone imports were already ahead, month on month, of their 2019 levels.

Brexit probably played some part in that. When the UK left the European Union at the start of 2020, nobody was too sure what it would mean and there was a general feeling that it could result in a drop in sales, so orders of goods being imported were reduced.

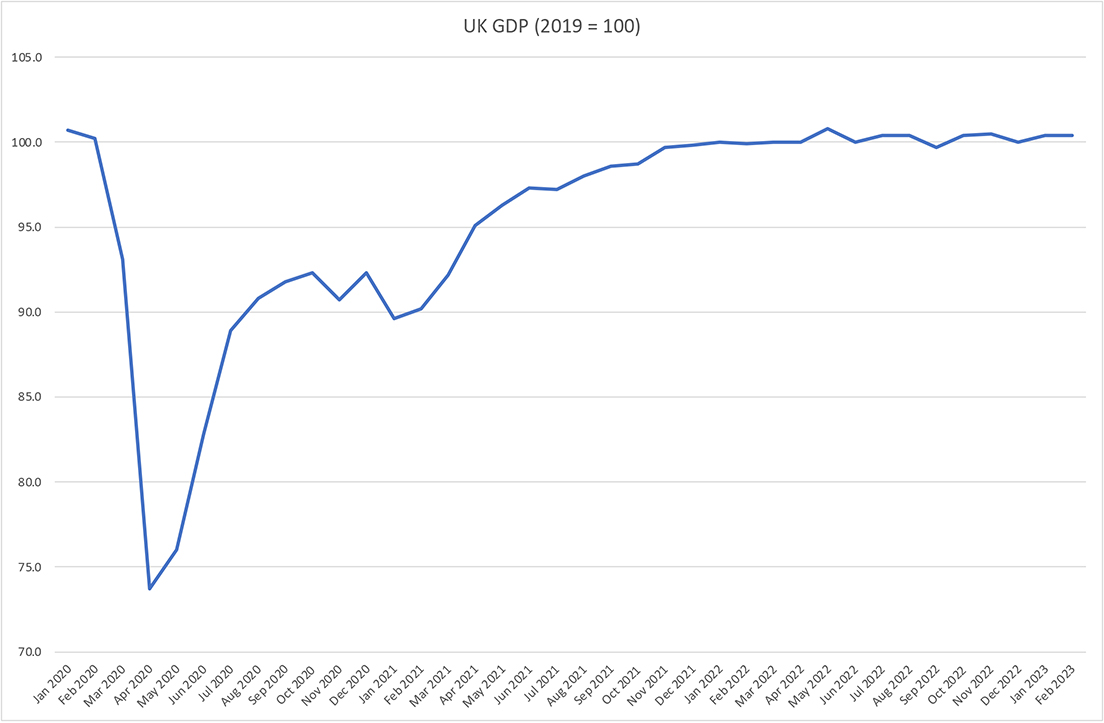

As it turned out, whatever the impact of Brexit might have been, it was lost in the impact of the Covid-19 effect, which saw the biggest fall in UK GDP since the 'Great Freeze' of 1709.

Construction was hit worst. It saw the biggest fall of any sector by a considerable margin, according to the Office for National Statistics (see graph below).

On the other hand, it had the best recovery and by the end of the year was almost back to where it had started the year, while the rest of the economy still lagging further behind.

Some companies did not shut down even during the first lockdown. It tended to be the big national builders that closed sites, while some local builders carried on working and stone companies carried on supplying them, even in the face of the occasional over-zealous police officer reportedly slapping on a spot fine, believing that building workers were not essential industries.

The government did not help because it did not declare that construction workers were essential, but Alok Sharma, at that time Secretary of State for the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, did write an open letter on 31 March praising construction companies for continuing to work, which he said was in line with the Chief Medical Officer's advice.

Still a little ambiguous, but construction sites did start to open again afterwards and most of the rest had resumed work by the time the pubs re-opened in July. Of course, that led to a rise in Covid-19 outbreaks again and there was another lockdown by the time Christmas 2020 arrived.

The virus distracted people's attention from Brexit, although the end of the transition year (2020) of Britain leaving the EU did bring some disruptions at the docks as people tackled the new paperwork. That was compounded by a new computer system at Felixstowe taking time to get up and running properly, a blockage caused by coronavirus PPE that was apparently the wrong kind so the medical community did not want it, and a certain amount of increased activity as companies, including stone companies, stocked up in case there were any delays as a result of the new import regulations from Europe (which some firms said there were, including a difficulty in finding drivers to move stock from the docks).

It is perhaps a little early to tell exactly what the outcome of the coronavirus and Brexit will be. The government has put hundreds of billions of pounds into helping companies and their employees survive the impact of the events, which has helped to minimise the impact so far, although an extra 700,000 people, mostly younger people (under 35), did join the unemployed in 2020.

However, by the time the furlough scheme ended on 30 September 2021, demand for labour was high and a feared further increase in unemployment was not realised. In fact, unemployment fell to 3.9% by the end of 2021, where it had been before the pandemic in 2019. That is a level not previously seen since the 1970s.

Although the fall in imports to May 2020 were significant, by the end of the year most of the deficit had been recovered. The year as a whole was not as bad for the stone industry as the economic crash following the 2007-08 credit crunch had been in terms of the value of imports, and the indications are the recovery has been quick this time, which it was not after the 2009 contraction.

The value of UK stone imports has returned to an upward trend since 2012. There was some hesitation about taking projects live towards the end of 2015 and the first half of 2016 as the referendum in the UK on leaving the European Union approached. Since the result was announced that the UK was to leave the EU (Brexit, as it is known) after the vote on 23 June 2016, confidence seems to have returned to the market, even though the result was unexpected by most people. Stone companies were busy in the summer and autumn of 2016 and 2017. 2020 was the Brexit transition year as well as seeing the Covid-19 pandemic.

The stone industry in the UK before the coronavirus

According to data from HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC - the UK tax collector) there was a jump in the value of stone imports in August in 2016 following the Brexit vote, but to some extent this will reflect the increase in sterling prices being paid as a result of the fall in the pound following the referendum. However, importers and their customers had already been making significant changes in their buying patterns as a result of the economic crisis of 2008, buying more lower price stone from the Far East and less from Europe.

The value of UK stone imports has returned to an upward trend since 2012. There was some hesitation about taking projects live towards the end of 2015 and the first half of 2016 as the referendum in the UK on leaving the European Union approached. Since the result was announced that the UK was to leave the EU (Brexit, as it is known) after the vote on 23 June 2016, confidence seems to have returned to the market, even though the result was unexpected by most people. Stone companies were busy in the summer and autumn of 2016. Many were also busy for much of 2017, as is clear from the figures now in (the graph below showing the long term growth in the stone market in the UK was added in July 2018).

According to data from HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC - the UK tax collector) there was a jump in the value of stone imports in August in 2016 following the Brexit vote, but this will reflect the increase in sterling prices being paid as a result of the fall in the pound following the referendum. However, importers and their customers had already been making significant changes in their buying patterns as a result of the economic crisis of 2008.

According to the World Bank, the UK economy as a whole showed consistent growth since 2010 and greater growth for much of that time than seen in general in the developed world, due in no small measure to a rapidly increasing population. In the year to June 2016 UK population grew again by more than 500,000 to top 65million, with 335,600 of the extra people the result of net migration and, therefore, immediately economically active.

The UK population grew by 5million people in the decade to the end of 2018. The growth has been reflected in relatively strong construction activity, although in 2017 and 2018, following the Brexit referendum, Europeans have started to go home – there has been a net loss of slightly more than 100,000 people from the former Eastern European countries. Of the 165,000 EU27 nationals working in construction in the UK, the government number crunchers at the Office for National Statistics estimate that 71% are from the former Eastern European block and 10% from Ireland.

With the Brexit vote out of the way, investment and consumer spending on property seem to have soared ahead, encouraged by government schemes and the removal of stamp duty (a tax on house purchases) on lower end housing. Natural and engineered stone supplied by stone companies remain materials of choice for commercial properties, home repair, maintenance & improvement (RMI) and higher-end new build housing, as well as hard landscaping, conservation work and memorials.

Most stone (and a still growing proportion), by volume and value, comes from India and China. Other significant areas that stone in the UK comes from include Turkey and, increasingly, the Middle East and North Africa, especially Egypt.

More stone is being used in construction in the UK all the time – for cladding, interiors, hard landscaping and roofing (almost all slate, mostly from Spain and Portugal). The figures here also include memorials. There was a spike in the value and volume of stone landed in the UK from overseas in 2008, followed by a fall after the economic crash and then a return to growth, although the prices being paid for it have fallen considerably.

The figures shown here do not represent all the stone coming into the UK because of the way they are collected. Natural Stone Specialist magazine has produced the graphs from figures using the most relevant commodity codes used by HMRC. We believe this will include the majority of stone coming into the UK while excluding other materials, and the same data sets are used for each year to produce meaningful comparisons.

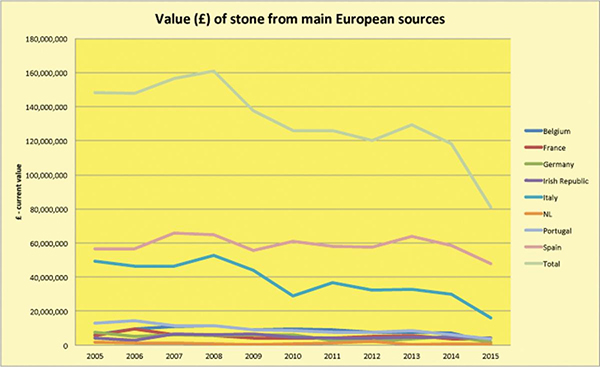

One of the most striking changes since the economic crisis of 2008 is the fall in the price of stone, although it lagged behind the crisis (understandably). This reflects the increasing proportion of stone coming from low cost parts of the world rather than Europe, the bargaining strength of the UK as its economy recovered quicker than most of the rest of the world after 2008, and a fall in world prices of stone reflecting a fall of international demand, especially in America, although that has since recovered. It is also partly a consequence of the strength of the hard landscaping sector, which has grown faster than most other sectors and uses stone that is typically less expensive than that used in other sectors (polished marbles and granites used for interiors and memorial stones are more expensive than granite and sandstone paving and walling).

The value of stone coming into the UK is calculated in sterling prices at current values (ie the exchange rate at the time the value was recorded). The fall in the value of sterling of 20% and more against major foreign currencies following the Brexit referendum vote in June 2016 will clearly have put up these prices, although, anecdotally, suppliers gradually passed those increases on rather than putting up prices by the full amount straight away. Overseas suppliers also took some of the hit, so the prices of stone landed in the UK were not immediately much higher.

For the whole of 2016, the value of stone imports, according to the commodity codes used here, was £413million, about 5.5% more than in 2015. That was for 4.2million tonnes of stone, up 10.5% on 2015. Compared with 2008, that was 96% growth in volume but, due to the steady fall in the prices of stone arriving in the UK, meant the value of the stone was actually less than in 2008 (a fall of 3%). One reason for the fall in prices is because less stone came from Europe - down 26% by volume. A substantial amount of the stone still coming from Europe is roofing slate from Spain and granite setts from Portugal for landscaping. It is the more expensive polished marble and finished masonry that has seen most of the downturn, so the average price of stone from Europe has fallen 40% since 2008. From the rest of the world the fall in price is 18.6%.

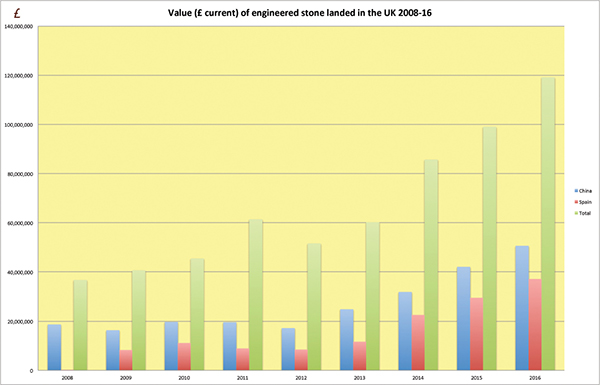

It is not possible these days to consider the interiors stone market without including engineered stone (the same is also starting to become true for hard landscaping). Engineered quartz is now a staple of the kitchen worktop market, and with the latest 'industrial' and 'marble' looks, quartz is becoming more commonly used in domestic and commercial settings outside of food areas as well. There is also an increasing number of other engineered stone products coming on to the market. The rise in this sector is plotted on the graph here. Again, it is not the full story because of the limitations of the HMRC commodity codes, but it shows the trend. The rapid growth in the amount of material from Spain reflects the success of market dominating Silestone from Spanish company Cosentino, which has also now added Dekton superdense surfaces.

The indigenous stone extraction industry in the UK (mining and quarrying) is poorly recorded. It consists of about 250 active, mostly small opencast and underground quarries, many of them small enough to be exempt from having to disclose their accounts publicly. The sector is considered too small for figures about its value to be published as it is felt it would be commercially sensitive. The Minerals Product Association (MPA) dimension stone section, which comprises quarry operators, produced a leaflet in 2015 trying to provide some answers. It valued UK dimensional stone sales at a rather flattering £350million in 2010, when, exceptionally, sales topped 2million tonnes (they are more usually around 1million tonnes a year). One of the reasons for the extra demand was the number of exceptionally rich foreigners who wanted to build mansions in the relative political calm of the UK. There were also plenty of rich British people who took advantage of some bargain prices during the recession to build themselves large houses and modernise and extend existing houses. They used indigenous stone because they liked it and, sometimes, because planners insisted they should. The flattering value of the British stone is a reflection of the high price of finished worked masonry used in the construction of the mansions. You can download a PDF of the MPA report by clicking on the link at the end of this report.

On the other hand, there is a trend towards using more indigenous stone and it is not just in the UK. According to the XXVIII Rapparto marmo e pietre nel mundo 2017 / 28th Report Marble and Stones in the World 2017 (the latest version of which you can buy here) there is a worldwide trend towards using local services and often (although less so in the UK) materials. The reason, according to the report, is that after substantial investment in technology for a protracted (and on-going) period, professional manufacturing is almost universally available.

Most of the building stones of the UK are limestones and sandstone, with a few areas of slate and granite. There are hardly any truly metamorphic marbles in the British Isles, although Ireland does produce some – Connermara Marble and Armargh Marble – and there is some in Scotland, although it is not currently produced as dimensional stone.

According to The Wall Cladding Market Report – UK 2016-2020 Analysis published by AMA Research, the UK market for wall cladding increased by around 18% in total between 2012 and 2015/16, driven by strong growth in new build and major refurbishment activity in key sectors, such as housebuilding, offices, schools & higher education, hotels & leisure, transport buildings and online retail warehousing. Clearly some of those sectors are not going to be using much stone. The range of cladding types is broad and the supply chain diversified and fragmented.

Indigenous stones comprise the smaller part of the stone industry in the UK and most years 75-80% of the stone used is imported. However, because it is such a small market, one or two large projects using British stone can result in significant fluctuations in the amount of indigenous stone used in any one year.

Larger quarry operators and stone processing companies have been on a spending spree in the past four-or-five years, investing in new premises, machinery and plant. Many had put investment decisions on hold between the crash of 2008 and the start of 2014 and the surge of investment since then has included an element of catch-up.

Stone companies' customers, particularly in the commercial sector, had also put spending decisions on hold, which led to a pent up demand that suddenly uncoiled in 2014. It is one of the reasons for a jump in stone imports that year. Major commercial and landscaping projects coming on stream in London and other major cities caused a surge in demand for stone.

The use of stone in the UK diminished in the first three quarters of the 20th century but has since enjoyed a major revival and demand for it continues to grow strongly as the UK recovers from the economic crash that started with the credit crunch of 2007-8. In 2009, when banks withdrew their support from a lot of companies, about a quarter of the 1,200 granite worktop companies then operating went out of business.

There has been a gradual recovery since 2012/13 that has seen more new companies come into the sector, including some of the kitchen companies opening their own stone worktop factories. Companies that went bust in 2009 and subsequently have sometimes spawned more than one replacement as people who worked for them have set up new companies. There are about 1,100 companies in the UK now making worktops, ranging from memorial masons who have moved into the sector making the occasional top (less than one a week) to major companies making 100 or more worktops a week, these days more than half of them in engineered stone, including the new sintered and porcelain products such as Dekton, Lapitec and Neolith, but mostly the now widely used engineered quartz.

Fashions change – most granite worktops installed at the turn of millennium were dark colours, but gradually lighter and more lively colours are growing in popularity. Many would like marble in their kitchens but are put off because marble is easily stained and etched. The makers of engineered quartz and, more recently, sintered products such as Lapitec and Dekton and sheet ceramics, are capitalising on this by making products that look more like light-coloured marble but with the strength of granite. Many stone companies supplying worktops these days find half or more of their sales come from quartz.

As the UK construction industry started growing out of the recession following the credit crunch of 2007-08, demand for stone started to strengthen from 2012. The use of stone is now well established in all areas of construction – commercial and domestic, for cladding and walling, flooring, worktops, wall coverings, features such as fireplaces and attention grabbing stairs (especially cantilevered stairs and landings).

Hard landscaping has also turned to stone in a major way, both for public and private projects. In 1980 stone paving and walling was a rarity. Now it is only a question of which stone to use. The big change was a huge increase in sandstone from India (in particular) and granite from China (in particular). The low price of these products, coinciding with a growing awareness of the importance of the spaces between buildings and an explosion of major urban regeneration programmes, brought about a sea change in the aesthetic for urban spaces. A driver has been the appreciation by local administrations that simply improving the urban landscape can act as an impetus to a lot of private sector investment in the buildings in an area. This has been the rationale for many urban landscape projects.

Britain and Ireland have a long history of building with stone, with villages and monuments still standing that date back to pre-history – the most famous of which is probably Stone Henge on Salisbury Plain in the south of England, although others, notably Skara Brae in Scotland and New Grange in Ireland, are more impressive to visit.

The Roman conquest and 400-year occupation of Britain left us with stone fortifications and mansions. The Norman invasion of 1066 brought a burst of castle and church building, although it had begun before William the Conqueror turned up at Hastings as religious orders established their cathedrals and monasteries across the land and the nobility sought to build secure fortresses.

Stone has always been chosen for structures that are intended to show solidity and permanence, marking out the finest in architecture through the centuries.

With the rise of modernism at the start of the 19th century, architects turned to the then newly developed hard concretes, but as the second millennium drew to a close, architecture in Britain rediscovered its love of stone. Once again, the very symbol of permanence and longevity was chosen to mark out significant buildings and landscapes intended to give the impression of being intended to last for the next 1,000 years. The UK Government made £5billion available to help pay for millennium projects, giving the economy a boost into the third millennium AD.

Stone continues to be popular, although inevitably sales fell as a result of the world credit crunch and economic crisis of 2007-8.

Between 2008 and 2009, GDP per head in the UK dropped by 5.5%, the largest annual decrease since 1949, another period of austerity. The number of houses being built more than halved and banks withdrew their support for many businesses. The value of stone imports fell 16% in 2009 from what, taken over the long term, now looks like the bubble of 2007-8.

Before the crash there had been a big increase in the number of companies moving into the production and installation of granite kitchen worktops. By 2009, when the economic downturn really hit, there were about 1,200 companies templating, making and installing worktops and the crash saw about a quarter of them go out of business as demand rapidly fell. Many kitchen studios closed and with them their worktop suppliers.

Prompted by lifestyle magazine articles and television programmes, granite and, later, engineered quartz worktops had become de rigueur. New builds and home improvements alike just had to have granite worktops. Limestone floors also became popular, as well as stone and marble features such as fireplaces. More recently, stone and marble walls, floors and vanity units have become popular for bathrooms and wet rooms, and stone is more frequently seen in bedrooms and living areas.

In commercial buildings, the City of London leads the way in the use of stone for cladding and masonry on its offices, and stone and marble in its interiors, especially in public areas of foyers and toilets. But all major cities aspire to have stone marking their centres of administration, commerce and entertainment.

Many contractors still turn to Italy as a centre of stone selection and source for major projects in the UK, although Spain, Germany and France also supply cladding and masonry for new build and conservation projects in the UK and, of course, the British Isles produce their own stones, although indigenous stone accounts for about 25% only of the market these days.

While larger stone contractors such as Szerelmey, PAYE, Stonewest, Livra, APS, Vetter, Mather & Ellis, Ketton, William Anelay and many more, as well as major interiors companies do buy their stone directly from suppliers all over the world, the recession made companies think again about holding expensive stock and more returned to the traditional supply chain of established international and national wholesalers such as Pisani, Levantina, The Marble & Granite Centre, Gerald Culliford, Beltrami, B-Stone, MGLW, Cosentino, International Stones and many others, as well as specialists in hard landscaping, roofing and memorials. They are listed with full contact details in the Natural Stone Directory, which can be bought online from this website.

After the crash of 2009 there was a dead cat bounce in 2010, and adjustment back down in 2011. There followed three years of growth, with volume outpacing value, reflecting the strength of sterling ahead of the Brexit vote and, perhaps, a hardening of attitudes by buyers, not to mention a fall in demand in China.

According to the figures from HM Revenue & Customs, the value of imports in 2014 grew a little more than 2% to just over £400million for nearly 3million tonnes of stone. Figures for UK stone production (mostly limestone and sandstone and a little granite) are sketchy. However, according to the British Geological Survey, UK production was a little under 1million tonnes.

An upward trend in the market is clear, reflecting both the growth in British construction (up 7.4% in 2014) and the economy in general (up 2.8%).

Direct imports from India and China continue to grow and for the first time in 2014 the two countries supplied more than half the UK's stone imports. India still supplies most. Turkey also supplies a significant amount of marble and limestone, although with the decline in popularity of travertine for domestic floors, a lot of which came from Turkey, its imports have declined a little.

Spain has maintained its position as a major supplier of stone to the UK, not least because it ships a lot of roofing slate to Britain as well as granite for hard landscaping. In 2014 it was the source of 138,000 tonnes of natural stone products valued at £58million.

Italy's importance as a supplier to the UK has been diminishing, slowly but inexorably, for many years. At the height of the market in 2008 it shipped 51,000tonnes of stone to the UK valued in sterling at £52million. In 2014 that was 31,000tonnes worth £30million, according to MH Revenue & Customs.

Italy is still respected for its high quality finished stone and many developers continue to turn to Italy to source large quantities of natural materials for top-of-the-market projects, but clearly alternative sources are also being used.

Notes:

-

The usual caveats apply to these figures: they are based on tax returns (mostly VAT) and some products can slip through under different product categories, so do not show up as stone imports. No doubt some stone that would not normally be considered part of the stonemason's repertoire is also included. Nevertheless, the figures are comparable over time and provide the best source of information available to the industry about trends in the use of natural stone.

-

No independent value is reported for the indigenous stone industry in the UK, which has about 170 quarry and mine operators supplying dimensional stone extracted from about 300 opencast and underground quarries in the British Isles. The stone is used almost exclusively for the home market, although a little is exported. Some goes overseas to be processed before returning to the UK.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Minerals Product Association Dimension Stone Report | 1.46 MB |